- MAIN INDEX: Adolf Hitler Death and Survival: Legend, Myth and Reality

- New Evidence exposes Hitler’s Secret Refuge after World War II

- Did Hitler Die in the Bunker or Did He Flee to Argentina?

- Is This the Final Proof That Hitler Escaped to Argentina?

- Escape to Argentina

- Following in the Footsteps of Hitler

- Hitler and the Mysteries of the Gran Hotel Viena

- Unredacted FBI File 65-53615

- Declassified CIA File on Hitler

- Hitler's Escape

- Hitler's Escape to South America

- Hitler is Alive

- 17 August 1945

- U-Boote

- Research on Hitler's Escape

- Argentina was Hitler’s Final Home

- "Hunting Hitler"

- Fantastic Voyage of the U-977

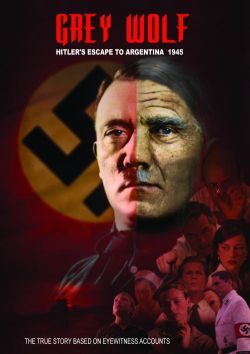

- "Grey Wolf – The Escape of Adolf Hitler"

- Hitler Escaped To Argentina Theory

Excerpt from "Grey Wolf – The Escape of Adolf Hitler" by Gerrard Williams and Simon Dunstan

The turning point against Germany during World War Two was not the loss of the Battle of Britain or the mounting of D-Day on Normandy's shores.

While the air battle over London was an important German defeat that allowed Britain to fight on -alone at the time- other than as a moral victory, taking the islands of the United Kingdom would have had little strategic value to Germany before the United States joined the conflict.

And by the time Allied soldiers stormed the beaches of northern France, the tide of war had already turned against the Nazi horde.

D-Day, while imperative and impressive, was actually the beginning of massive mop-up operations.

During the autumn and winter of 1942, Germany suffered the most pivotal defeat of the war at the Battle of Stalingrad.

From that day on, the outcome of the war was almost fixed. And almost everybody knew it.

Until the moment when Hitler looked up from the strategic objective he was pursuing in The Soviet Union, the oilfields and refineries of Ukraine to fuel his war machine, Germany was wnning the war.

On 5 April 1942, Hitler’s goal was to eliminate Soviet forces in the south, secure the region’s economic resources, and then wheel his armies either north to Moscow or south to conquer the remainder of the Caucasus. One of the ironies of the war, is that the German Sixth Army need not have got entangled in Stalingrad, but on 9 July Hitler altered his original plan and ordered the simultaneous capture of both Stalingrad and the Caucasus.

The Führer could not resist the moral victory that taking "Stalin's City", now so close, would be. Planning a quick campaign that would take mere weeks, he swung his Sixth Army from its course southward toward the oilfields and refineries, turned them to the northeast, and attacked. The bold move was at first successful and Stalingrad was captured. But in the frozen winter months of 1942-43, a four million-man Russian army surrounded the 330,000-man force of General Friedrich von Paulus.

By the time Paulus surrendered, SS forces had barely been able to break through and rescue only 5,000 survivors. The rest were force-marched to Siberia and most never heard from again. After the moral loss at Stalingrad and the tactical loss of oil to feed the hungry Nazi war machine, ultimate surrender for Germany was just a matter of time, barring an unforeseen miracle.

Martin Bormann, true to his proven, pragmatic ways, was uniquely prepared to deal with the former eventuality, and possibly capable of providing the latter. Through his old friend at the Reichspost, Wilhelm Ohnesorge, it appears likely he was supporting a program that could furnish the miracle needed - Manfred von Ardenne's Uranium enrichment program. The program just required enough time.

Karl Wilhelm Ohnesorge was a German politician in the Third Reich who sat in Hitler's Cabinet.

From 1937 to 1945, he also acted as the minister and official of the Reichspostministerium [RPM, Reich Postal Ministry], Reichspost. Along with his ministerial duties, Ohnesorge also significantly delved into research relating to propagation and promotion of the Nazi Party through wire signals and radio, and became known as something of a technician for his work in making the latter technically possible.

He is also known to have contributed heavily to research towards a German atomic bomb, and he presented many designs and diagrams of his ideas to Hitler himself, with whom he had developed a personal companionship.

Manfred von Ardenne's research on nuclear physics and high-frequency technology was financed by the Reichspost. Von Ardenne attracted top-notch personnel to work in his facility, such as the nuclear physicist Fritz Houtermans, in 1940. Von Ardenne also conducted research on isotope separation.

During the denazification after the war, as a leading member of the Party, charges were brought against him. However, for unknown reasons, these charges were later revoked, and Ohnesorge was not penalized for his involvement with the Nazis. His life post-war remains undocumented.

On the other hand, if time should run out, the last thing that Martin Bormann would allow his Fatherland to endure was another rapacious war reparations assessment like that forced upon it after World War One. The Allies could kill the people, plunder the land, rape the women, and level the cities, but in his shrewdly insightful way, Bormann knew that they could not own Germany itself if they did not own Germany's wealth. In the spring of 1943, Bormann began to look for ways to conserve the Reich's riches if the war was lost.

He started with '"Aktion Feuerland" [Operation Fireland].

The treasure consisted of hundreds of millions of Reichsmarks; boxes and boxes of gold and platinum, pearls and diamonds; crates full of the priceless art of Europe; and billionaire bundles of stocks and other securities. The loot was amassed in a series of bank safes and underground vaults throughout the Reich - until Martin Bormann was made aware of its existence by one of his many internal intelligence conduits. In late 1943 he took control of much, though not all, of this booty and informed Hitler of its existence and a plan he had formulated for its conservation.

"Bury your treasure, for you will need it to begin a Fourth Reich," Hitler had responded. With that blessing, Bormann took control of at least six U-Boats, some of them unmarked, from Gross Admiral Karl Dönitz, and garnered the support of Generalisimo Francisco Franco to headquarter the U-Boats in the Spanish port cities of Cadiz and Vigo. The U-Boats for the next two years, supplied by cargo planes from Germany that transported the treasures to the coastal towns on the Atlantic, began a non-stop circuit transporting the treasure to the far southern reaches of Argentina - the region known as Tierra del Fuego, or Land of Fire, at Patagonia’s southernmost point. At their destinations they were unloaded by Bormann's mysterious minions and deposited into a variety of international bank accounts controlled by a cryptic cabal of Bormann partners.

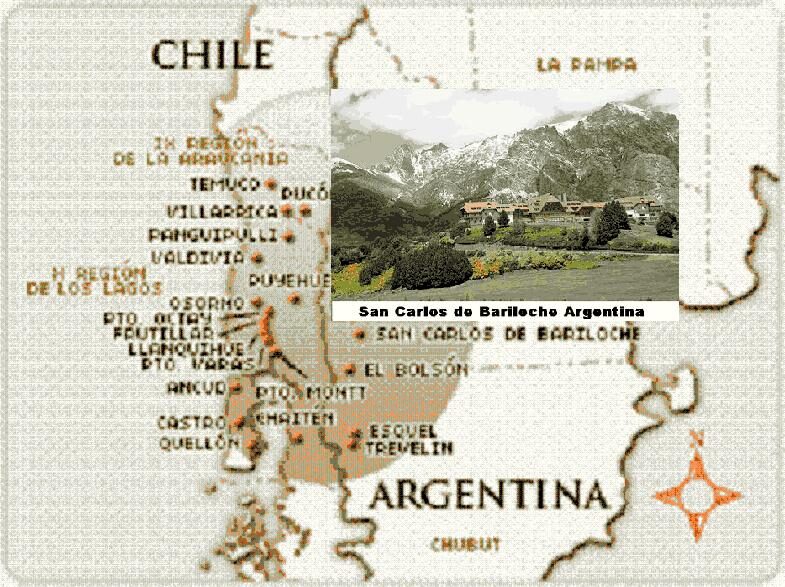

Another objective of the plan, was to create a secret, self-contained refuge for Hitler in the heart of a sympathetic German community, at a chosen site near the town of San Carlos de Bariloche in the far west of Argentina’s Rio Negro province.

The Nazis definitely had organized plans for a comeback.

At the center of the plan was Martin Bormann, the Reichsleiter.

Bormann had risen through the ranks to Party Secretary, the number two spot in the Nazi hierarchy. Hitler had entrusted Bormann with ensuring the Reich would be able to stage a comeback once hostilities ceased.

The meeting in the Red House was the beginnings of Bormann's effort to expand his plan to include industrialist and top ranking office. The meeting had been the result of Bormann’s order.

However, Bormann did not attend the meeting. The Treasury Department has a transcript of the meeting from a captured document.

Nazis Plotted Post-WWII Return

NEW YORK [Reuter] - Realizing they were losing the war in 1944; Nazi leaders met top German industrialists to plan a secret post-war international network to restore them to power, according to a newly declassified U.S. Military Intelligence document [Report EW-Pa 128].

The document, which appears to confirm a meeting historians have long argued about, says an SS general and a representative of the German armaments ministry told such companies as Krupp and Röhling that they must be prepared to finance the Nazi party after the war when it went underground.

They were also told "existing financial reserves in foreign countries must be placed at the disposal of the party so that a strong German empire can be created after the defeat''.

The document, detailing an August 10 August 1944 meeting, was obtained from the World Jewish Congress, which has been working with the Senate Banking Committee and the Holocaust Museum to determine what happened to looted Jewish money and property in the Second World War.

As a result of the probe, thousands of documents from "Operation Safehaven'' have been made public. The operation was a U.S. Intelligence effort to track how the German government used Swiss banks during the war to hide looted Jewish assets.

The three-page document, released by the National Archives, was sent from Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force to the U.S. secretary of state in November 1944. It described a secret meeting at the Maison Rouge [Red House Hotel] in Strasbourg, occupied France, on 10 August 1944.

The source for the report was an agent who attended and "had worked for the French on German problems since 1916".

Jeffrey Bale, a Columbia University expert on clandestine Nazi networks, said historians have debated whether such a meeting could have taken place because it came a month after the attempt on Adolf Hitler's life, which had led to a crackdown on discussions of a possible German military defeat.

Bale said the Red House meeting was mentioned in Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal's 1967 book "The Murderers Among Us'' and again in a 1978 book by French Communist Victor Alexandrov, ''The SS Mafia".''

A U.S. Treasury Department analysis in 1946 reported that the Germans had transferred $500 million out of the country before the war's end to countries such as Spain, Switzerland, Lichtenstein, Portugal, Argentina and Turkey where it was used to buy hundreds of companies.

“As soon as the [Nazi] party becomes strong enough tore-establish its control over Germany, the industrialists will be paid for their efforts and co-operation by concessions and orders,'' the intelligence document said.

The meeting was presided over by Dr. Friedrich Scheid, an SS Obergruppenführer and director of Hermsdorff & Schönburg Company. Attending were representatives of seven German companies including Krupp, Röhling, Messerschmidt, and Volkswagenwerk and officials of the ministries of armaments and the navy.

The industrialists were from companies with extensive interests in France and Scheid is quoted as saying the battle of France was lost and "from now ... German industry must realize that the war cannot be won and it must take steps in preparation for a post-war commercial campaign''. He also assured the gathering the "Treason against the Nation Law" about foreign exchange was repealed.

He said:

"German industry must make contacts and alliances with foreign firms and lay the groundwork for borrowing considerable sums in foreign countries".

He cited the Krupp company's sharing of patents with U.S. companies so that they would have to work with Krupp.

A representative of the armaments ministry presided over a smaller second meeting with Scheid and representatives of Krupp and Röhling, who were told the war was lost and would continue only until the unity of Germany was guaranteed. He said they must prepare themselves to finance the Nazi party when it went underground".

San Carlos de Bariloche, usually known as Bariloche, is a city in the province of Río Negro, Argentina, situated in the foothills of the Andes on the southern shores of

Nahuel Huapi Lake. It is located within the Nahuel Huapi National Park.

After development of extensive public works and Alpine-styled architecture, the city emerged in the 1930s and 1940s as a major tourism centre with skiing, trekking and mountaineering facilities, and has numerous restaurants, cafés, and chocolate shops.

The name Bariloche comes from the Mapudungun word Vuriloche meaning

"people from behind the mountain" [vuri = behind, che = people].

The area had stronger connections to Chile than to the distant city of Buenos Aires during most of the 19th century, but the explorations of Francisco Moreno and the Argentine campaigns of the Conquest of the Desert established the claims of the Argentine government. It thought the area was a natural expansion of the Viedma colony, and the Andes were the natural frontier to Chile. In the 1881 border treaty between Chile and Argentina, the Nahuel Huapi area was recognised as Argentine.

The modern settlement of Bariloche developed from a shop established by Carlos Wiederhold. The German immigrant had first settled in the area of Lake Llanquihue

in Chile. Wiederhold crossed the Andes and established a little shop called

"La Alemana" [The German]. A small settlement developed around the shop,

and its former site is the city center. By 1895 the settlement was primarily made up

of German-speaking immigrants: Austrians, Germans, and Slovenians,

as well as Italians from the city of Belluno, and Chileans.

A local legend says that the name came from a letter erroneously addressed to Wiederhold as San Carlos instead of Don Carlos. Most of the commerce in Bariloche related to goods imported and exported at the seaport of Puerto Montt in Chile.

In the 1930s the centre of the city was redesigned to have the appearance of a traditional European central alpine town [it was called "Little Switzerland"]. Many buildings were made of wood and stone. In 1909 there were 1,250 inhabitants; a telegraph, post office, and a road connected the city with Neuquén.

Commerce continued to depend on Chile until the arrival of the railroad in 1934,

which connected the city with Argentine markets.

Between 1935 and 1940, the Argentine Directorate of National Parks carried out a number of urban public works, giving the city a distinctive architectural

perhaps the best-known is the Civic Centre.

Bariloche grew from being a centre of cattle trade that relied on commerce with Chile,

to becoming a tourism centre for the Argentine elite. It took on a cosmopolitan architectural and urban profile. Growth in the city's tourist trade began in the 1930s, when local hotel occupancy grew from 1550 tourists in 1934 to 4000 in 1940.

In 1934 Ezequiel Bustillo, then director of the National Parks Direction,

contracted his brother Alejandro Bustillo to build several buildings in Iguazú and

Nahuel Huapi National Park [Bariloche was the main settlement inside the park].

Alejandro Bustillo designed the Edificio Movilidad, Plaza Perito Moreno, the Neo-Gothic San Carlos de Bariloche Cathedral, and the Llao Llao Hotel. Architect

Ernesto de Estrada designed the Civic Centre of Barloche, which opened in 1940.

During the 1950s, on the small island of Huemul, not far into lake Nahuel Huapi, former president Juan Domingo Perón tried to have the world's first fusion reactor built secretly. The project cost the equivalent of about $300 million modern US dollars, and it was never finished, due to the lack of the highly advanced technology that was needed.

The Austrian Ronald Richter was in charge of the project.

In 1995, Bariloche made headlines in the international press when it became known as a haven for Nazi war criminals, such as the former SS Hauptsturmführer Erich Priebke. Priebke had been the director of the German School of Bariloche for many years.

In his 2004 book "Bariloche nazi-guía turística", Argentine author Abel Basti

claimsthat Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun lived in the surroundings of Bariloche

for many years after World War II, in the estate of Inalco.

"Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler", a 2011 book by British authors Simon Dunstan and Gerrard Williams, proposed that Hitler and Eva Braun escaped from Berlin in 1945 and hid at Hacienda San Ramon, six miles east of Bariloche, until the early 1960s.

This account is disputed by most historians, who generally believe that Hitler

and Braun committed suicide in the last days of World War II.

At a smaller conference that afternoon, Dr. Bosse of the German Armaments Ministry indicated the Nazi government would make huge sums available to industrialists to help secure bases in foreign countries. Dr. Bosse advised the industrialists that two main banks could be used for the export of capital: Schweizerische Kreditanstalt of Zürich and the Basler Handelsbank. He also advised the industrialists of Swiss cloaks that would buy Swiss property for a five-percent commission.

The Intelligence report added that the meetings signaled a new Nazi policy "whereby industrialists with government assistance will export as much of their capital as possible".

Bormann knew the Nazis had lost the war once the Allies landed in Normandy on D-Day.

He gave himself nine months to place into operation his flight capital program to find a safe haven for the Nazis' liquid assets. Essentially, the Alsace-Lorraine area would serve as a microcosm for his plans. Germans owned the controlling interest in many of the French banks in the area. A German majority ownership also controlled many of the factories. In essence, Bormann would rely on "Tarnung" [Corporate camouflage, the art of concealing foreign properties from enemy governments], the magic hood that renders its wearer invisible. Bormann sorted his records and then shipped them to Argentina via Spain. Bormann began his flight capital, already having control of the Auslands-Organisation and the I.G. Verbindungsmänner. Both organizations placed spies in foreign countries disguised as technicians and directors of German corporations.

By the time, the Battle of the Bulge was raging, Bormann had already been very successful in moving assets out of Germany. In 1938, the number of patent registrations to German companies was 1,618 but after the Red House meeting it had risen to 3,377. Bormann had also created a two-price system with Germany’s trading partners. In it, the lower price was the price cleared or settled at the end of the banking day, the higher price was retained on the books of the neutral importer. The difference accumulated to a German account, becoming flight capital on deposit. Under this system Bormann amassed about $18 million kroner and $12 million Turkish lira. Balance sheets in Sweden showed Bormann acquired seven mines in central Sweden.

Bormann created 750 new corporations. The corporations were scattered across the globe and represented a wide array of economic activity from steel and chemicals to electrical companies. The firms were located as follows: Portugal 58, Spain 112, Sweden 233, Switzerland 234, Turkey 35 and Argentina 98. All the corporations created by Bormann issued bearer bonds, so the real ownership was impossible to establish.

Bormann had several means of dispersing the Nazi assets. He used the diplomatic pouches of the Nazi’s foreign policy minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, to send gold, diamonds, stocks and bonds to Sweden twice a month. A similar pattern was used to ferry more valuables to South America. In addition to Bormann’s Aktion Feuerland project, Bormann allowed other Nazis to transfer their own valuables through the same channels.

In Turkey, both the Deutsche Istanbul and the Deutsche Orient banks were allowed to retain all their earnings rather than send them back to Berlin. The earnings were mere book-keeping items that were ready to be transferred anywhere in the world.

In 1941, German investments in United States corporations held a voting majority in 170 corporations and minority ownership in another 108 American corporations. Additionally, American corporations had investments in Germany totaling $420 million. With his program for flight capital well on its way, Bormann gave permission for Nazis to once again buy American stocks.

The purchase of American stocks was usually done through a neutral country, typically Switzerland or Argentina. From foreign exchange funds on deposits in Switzerland and Argentina, large demand deposits were placed in such New York banks as National City, Chase, Manufacturers Hanover, Morgan Guaranty, and Irving Trust. Over $5 billion dollars of American stocks was purchased in such a manner. These same banks were active in supporting Germany. In addition, every major Nazi corporation transferred assets and personnel to their foreign subsidiaries.

This was called "Aktion Adlerflug" [Project Eagle Flight], an operation code name which involved setting up innumerable foreign bank accounts and investing funds in foreign companies that were controlled by hidden German interests.

The United States and Britain never could fully grasp the extent of the Nazi flight capital.

John Pehle provides an interesting insight to why the United States was unable to stop Bormann and his movement of Nazi assets to neutral countries. Pehle was the original director of the Foreign Funds Control.

Pehle’s reasoning was:

"In 1944, emphasis in Washington shifted from overseas fiscal controls to assistance to Jewish war refugees. On presidential order I was made executive director of the War Refuge Board in January 1944. Orvis Schmidt became director of Foreign Funds Control. Some of the manpower he had was transferred, and while the Germans evidently were doing their best to avoid Allied seizure of assets, we were doing our best to extricate as many Jews as possible from Europe".

Pehle’s explanation seems overly simple. Additional personnel would have been useful and more could have been accomplished. However, the real problem was the rot and corruption within the United States. The leaders of America’s largest corporations were all in sympathy with the Nazis and almost all of them had invested heavily in Nazi Germany. Additionally, there were many in Congress that sympathized with the Nazi cause. The mood in Congress was one of "get the boys home and get on with business".

When Orvis Schmidt testified before congress to the extent of the Nazi infiltration of neutral countries before the end of the war, it fell on deaf ears. An excerpt of his testimony states:

"The danger does not lie so much in the fact that the German industrial giants have honeycombed the neutrals, Turkey and Argentina, with branches and affiliates which know how to subvert their commercial interest to the espionage and sabotage demands of their government. It is important and dangerous however, that many of these branches, subsidiaries and affiliates in the neutrals and much of the cash, securities, patents, contracts and so forth are ostensibly owned through the medium of secret numbered accounts or rubric accounts, trusts, loans, holding companies, bearer shares and the like by dummy persons and companies claiming neutral nationality and all of the alleged protection and privileges arising from such identities. The real problem is to break through the veil of secrecy and reach and eliminate the German ability to finance another world war. We must render useless the devices and cloaks which have been employed to hide German assets.

"We have found an I.G. Farben list of its own companies abroad and at home--- a secret list hitherto unknown--- which names over 700 companies in which I.G. Farben has an interest".

The list referred to in the quote list does not include the 750 companies Bormann set up.

Following the war Schmidt testified again to congress as follows:

"They were inclined to be very indignant. Their general attitude and expectations was that the war was over and we ought now to be assisting them in helping to get I.G. Farben and German industry back on its feet. Some of them have outwardly said that this questioning and investigation was in their estimation, only a phenomenon of short duration, because as soon as things got a little settled they would expect their friends in the United States and England to be coming over. Their friends, so they say would put a stop to activities such as these investigations and would see that they got the treatment which they regarded as proper and the assistance would be given to them to help reestablish their industry".

Between 1943 and 1945 more than 200 German companies set up subsidiaries in Argentina. Bormann deposited money and other assets, such as industrial patents, were transferred through shell companies in Switzerland, Spain and Portugal to the Argentine branches of German banks such as the Banco Alemán Transatlántico. The funds were then channeled to the German companies operating in Argentina, such as the automobile manufacturer Mercedes Benz, the first Mercedes Benz factory to be built outside Germany. These companies were then charged the higher production costs of their German head office for products made in Argentina. Bormann acquired his own shipping lines, including the Spanish shipping company 'Compania Naviera Lavantina' and the 'Italian Airline Linee Aeree Transcontinentali Italiane', or LATI. This gave Bormann his own independent pipeline to move people to Spain and from Spain to Argentina without having to use German Luftwaffe plane.

Statistics recently issued by the British Ministry of Economic Warfare estimate that the Nazis looted close to $27,000,000,000 from the conquered European nations. Much of this loot was used to pay for the war effort, but a large portion was still intact and in Nazi hands as the end of the war neared. The Nazi Party and the S.S., as organizations, got away intact. They got away with the money, the Reichsbank treasury, $15,000,000,000 in 1945 money. Guinness calls it the world's largest unsolved bank robbery in history. Then there was all the stolen art, pieces of which, to this day, occasionally surface.

It is easy and profitable to blame a dead, "crazy" man for one's mistakes and crimes. Hitler has assumed mythic proportions since his death. In life, he was mainly a front man, a mouthpiece, a lightning rod, and above all, the Nazi's "great communicator".

While the masses worshipped him like a god, his friends plotted behind his back, used him as a cat's paw and scapegoat, and [perhaps] cynically sacrificed him to save their own skins and fortune. Hitler had cleverly parlayed his position as figurehead into control over the military by rewording the soldiers oath. However, military power has always been subordinate to economic power. The purse strings of the Nazi Party were controlled by Bormann.

Bormann had help from his friends, like Herman Abs.

While Germany's bankers were collectively responsible for the financing of Hitler's war effort, the dean of them all is Herman Josef Abs. Money was his life, and his astuteness in banking and international financial manipulations enabled Deutsche Bank to serve as leader in fuelling the ambitions and accomplishments of Adolf Hitler and Martin Bormann. His dominance was retained when the Federal Republic of Germany picked itself up from the ashes; he was still there as chairman of Deutsche Bank, director of I.G Farben, and of such others as Daimler-Benz and the giant electrical conglomerate, Siemans. Abs became a financial advisor to the first West German chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, and was a welcome visitor in the Federal Chancellery under Mr. Adenauer's successors, Ludwig Erhard and Kurt George Kiesinger ... ... [Bormann's] friendship with Dr. Herman Josef Abs predated Abs's move into the management of Deutsche Bank. Dr. Abs had been a partner in the prestigious private bank of Delbruck, Schickler & Co. in Berlin.

Recalling those days, Abs has written: "The Reich Chancellery in Berlin was its largest account, and it was through this account that Adolf Hitler received his salary as Chancellor of the Reich".

Reichsleiter Bormann knew that his relationship with Abs would tighten as his own power grew. He knew in 1943 that with his Nazi banking committee well established, he had the means to set new Nazi state policy when the time was ripe for the general transfer of capital, gold, stocks, and bearer bonds to safety in neutral nations.

Under the direction of Dr Herman Josef Abs [who never became a Nazi] the Deutsche Bank was responsible for financing the slave labour used by business giants such as Siemens, BMW, Volkswagen, I.G. Farben, Daimler Benz and others. The banks wealth quadrupled during the twelve years of Hitler's rule. Arrested by the British after the war for war crimes, he was quietly released after the intervention of the Bank of England to help restore the German banking industry in the British zone This caused much dissension between the British and the Americans who wanted the German Economy crushed.

This is the same Hermann Abs who was chosen by Pope John Paul II to oversee the reorganization of the Vatican Bank when it was caught red-handed laundering counterfeit securities and heroin profits for the Gambino crime family. It is worth noting that in his youth John Paul II was, according to the official version, once a slave labourer for I.G. Solvay, a Farben subsidiary specializing primarily in pharmaceuticals. He is supposed to have laboured in the Solvay quarries near Auschwitz. It's a rare slave indeed who becomes Pope at all, let alone then hires his former master to keep track of his money. Wonders truly never cease.

In October 1978 the Marshall Foundation was utilized as a platform for Dr. Herman J. Abs, now honorary president of Deutsche Bank A.G. as he addressed a meeting of businessmen and Bankers and members of the Foreign Policy Association in New York City on the 'Problems and Prospects of American-German Economic Co-operation.' This luncheon was chaired by his old friend, John J. McCloy, Wall Street banker and lawyer, who had worked closely with Dr. Abs when McCloy served as U.S. High Commissioner for Germany during those postwar reconstruction years. At that time, Hermann Abs, as chief executive of Deutsche Bank was also directing the spending of America's Marshall Plan money in West Germany as the chairman of the Reconstruction Loan Corporation of the Federal Republic of Germany.

This is the same McCloy who designed the Pentagon building and served on the Warren Commission. While Undersecretary of War, he had forbidden bombing of the rail lines to Auschwitz on the grounds that it might provoke retaliation against the Jews. One cannot but wonder what he had in mind.

Auschwitz was intended, first and foremost, to be a synthetic rubber and synthetic fuel factory complex. The more well-known dead Jews were to be merely a by-product. Abs had arranged the financing of its construction. In charge of synthetic rubber production was Otto Ambros, who also developed the root technology on which magnetic data storage is based. He was convicted of 25,000 counts of slavery and mass murder, and was sentenced to eight years in prison. After three and a half years, McCloy freed him. The head of the W.R. Grace & Co., J. Peter Grace [a Knight of Malta] hired Ambros as a research chemist and petitioned Congress to allow his emigration to the United States. This is the same J. Peter Grace who President Reagan appointed to head the so-called 'Grace Commission. to make the United States government more "efficient'.

-- "Esquire", 19 December 1978

More than Nazi money went underground.

Himmler was quoted as summing up his talk with Bormann to his most trusted lieutenants in these words: "It is possible that Germany will be defeated on the military front. It is even possible that she may have to capitulate. But never must the National Socialist German Workers' Party capitulate. That is what we have to work for from now on".

--"The Nazis Go Underground", by Curt Riass, Doubleday, Doran, and Co., Inc. 1944

Ex"-S.S. men infiltrated, among other things, every major Intelligence apparatus on earth. They have been major players in postwar history.

Spymaster Reinhardt Gehlen, for example, created the rationale for starting the Cold War out of whole cloth. As we now know, had the Red Army actually been intending to continue their drive westward, as Gehlen said they did, they would not have been tearing up railroad track in front of themselves. They relied heavily on rail to transport their troops. Our leaders didn't know; they believed Gehlen, and acted accordingly. Or they knew, and they lied to us. There is no third possibility. This comes as no surprise to those who have actually studied war.

Truth is the first casualty.

"Adolf Hitler's top Iintelligence officials worked with U.S. Intelligence officials during World War II, according to a transcript made available of secret testimony by Allen Dulles before a House Select committee in 1947".

-- "UPI", 29 September 1982

This is the same Dulles who served on the Warren Commission, investigating the assassination of the President who had fired him just prior to the murder in Dallas that enabled the success of the coup of '63. It is interesting to note that Dulles's law firm, Cromwell and Sullivan, also represented I.G. Farben before the War.

The Nazis did very well in the war, from a business viewpoint. War is a business. It is fought for material gain. The Nazis gained materially, and lived to spend it thus, they won the war. What they lost was territory. What they gained was treasure, new friends, and experience. The treasure included a couple of U-Boats full of bearer bonds, numbered stock shares and patent certificates.

This represented:

"... the hard core of Nazi wealth in Latin America. In 1944 a great treasure had been sent secretly across the Atlantic, the famous "Bormann treasure". This operation involved the transport from Germany to Argentina of several tons of gold, some securities, shares, and works of art ...

"... Several U-Boats arrived in Argentine waters after the capitulation of Germany. They were the carriers of bundles of documents, industrial patents, and securities. On 10 July 1945, the U-530 surfaced at the mouth of the River Platte and entered the port of La Plata. The following month, on 17 August, the U-977 also arrived at La Plata. In accordance with international conventions, both U-Boats were interned by Argentina and later handed over to the United States authorities.

"To the surprise of few, they were found to be empty of treasure. Two more U-Boats, according to reliable sources, appeared off an uninhabited stretch of the coast of Patagonia between 23 and 29 July 1945".

-- "The Avengers", by Michael Bar-Zohar, Hawthorn Books, 1967

In occupied Germany one could neither vote with these shares nor could one collect interest, dividends, nor royalties. When [West] Germany again "took its place among the nations of the World" in 1955, the Bundestag immediately changed all this. The holders of these once worthless scraps of paper suddenly, once again, possessed incredibly wealth.

Where was Hitler’s body?

This was the question asked by the first Soviet troops to enter the Führerbunker on 1 May 1945. A few days earlier, on 29 April, a special detachment of the SMERSH [NKVD counterespionage] element serving with the headquarters of the 3rd Shock Army had been created at Stalin’s insistence, specifically to discover the whereabouts of Adolf Hitler, dead or alive. The SMERSH team arrived at the Reich Chancellery moments after its capture by the Red Army. Despite intense pressure whereabouts of Adolf Hitler, dead or alive. The SMERSH team arrived at the Reich Chancellery moments after its capture by the Red Army. Despite intense pressure from Moscow, its searches proved fruitless. Although the charred bodies of Josef and Magda Göbbels were quickly found in the shell-torn garden, no evidence for the deaths of Adolf Hitler or Eva Braun was found.

Close behind the assault troops and NKVD officers, a group of twelve women doctors and their assistants of the Red Army medical corps were the first to enter the Bunker in the early afternoon of 2 May. The leader of the group spoke fluent German and asked one of the four people then remaining in the Bunker, the electrical machinist Johannes Hentschel, "Wo ist Adolf Hitler? Wo sind die Klamotten?" ["Where is Adolf Hitler? Where are the glad rags?"]. She seemed more interested in Eva Braun’s clothes than in the fate of the Führer of the Third Reich. The failure to find an identifiable corpse would vex the Soviet authorities for many months, if not years.

Apart from the Vorbunker’s above-ground access to the Old Chancellery building, three tunnels provided the upper Vorbunker with underground links. One led north, to the Foreign Office; one crossed the Wilhelmstrasse eastward, to the Propaganda Ministry; and one ran south, linking up with the labyrinth of shelters under the New Chancellery. However, the Old Chancellery—a confusing maze of passages and staircases, much altered over the years—also had an underground emergency exit to a third, deeper, secret shelter, known to only a select few. Hitler maintained his private quarters in the Old Chancellery throughout the war until forced underground in February 1945. To get to the secret shelter, Hitler did not have to leave his private study: as part of Hochtief’s extensive underground works, a tunnel had been built that connected Hitler’s quarters directly with the shelter. The tunnel was accessible via a doorway covered by a thin concrete sliding panel hidden beside a bookcase in the study. This tunnel, in turn, was connected to the Berlin underground railway system by a five-hundred-yard passageway. The third shelter had been provided with its own water supply, toilet facilities, and storage for food and weapons for up to twelve people for two weeks. Bormann had never really planned for it to be used; it was simply one of the range of options available to get Hitler out of Berlin. But by 27 April 1945, it was the obvious means of escape to take the Führer away from the devastating shells that were raining down on the government quarter of Berlin as Soviet troops fought their way in from three directions.

During the month of May 1945 after Germany had surrendered, Russian criminologists, guided by Major Ivan Nikitine, chief of Stalin's security police, reconstructed Hitler's last days in Berlin.

In those days, according to an article in "Time magazine" of 28 May 1945:

"A removable concrete plaque was found next to a bookshelf in Hitler's personal quarters. Behind it there was a man size tunnel which led to a super secret cement refuge 500 metres away. Another tunnel connected it with a tunnel belonging to a line of the underground/tube. Remains of food indicated that there had been between 6 and 12 people there until 9 May 1945".

The knowledge of this secret passage tells us nothing. We do not know who used to save their skins. Only free access to Russian archives which remain secret, will allow us to know the details about that hidden "emergency exit" which enabled escape from the underground refuge.

However, why would a man of Hitler's ambition, drive and rampant egomania spend years building escape tunnels throughout Berlin and then refuse to use them when the time came to do so.

According to the "Express", in the midst of shooting the program 'Hunting Hitler', a new eight-part documentary on the "History Channel" a secret false wall was found in a Berlin subway station. This then led the show to hypothesize that Adolf Hitler used this to escape from Nazi Germany, which at the time of his alleged suicide had been surrounded by the invading Russian troops.

The discovery of the above tunnel proves that Hitler could have traveled from the Bunker where he is believed to have killed himself in, all the way to Tempelhof Airport underground. For years there was a clear passage from the Bunker to the airport, except for the final 200 yards. Now, with the discovery of this hidden tunnel, the final connection has been unearthed..

Designed by Hitler's favorite architect, Albert Speer, the New Reich Chancellery was to have been the seat of power of the Thousand-Year Reich. During the war as the Allied bomber offensive intensified, the Führerbunker was built to protect Hitler from the increasingly devastating aerial bombs employed by the RAF and USAAF.

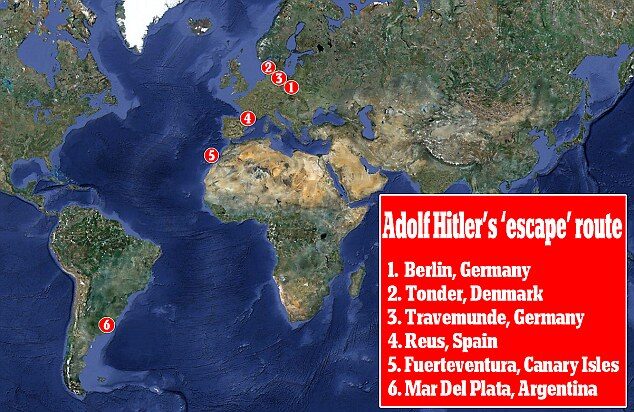

In the final months of the war, Adolf Hitler retreated to the depths of the Führerbunker beneath the Old Reich Chancellery; Bormann had organized a secret tunnel that allowed the Führer and his select companions to escape via the Berlin subway system to an improvised airstrip and flee to Denmark and onward to Spain and Argentina. There had been opportunities aplenty from 21 April on, but Hitler’s refusal to leave earlier had limited Bormann’s carefully planned options. Nevertheless, on 27 and 28 April there were still potentially feasible land routes out of Berlin. The army commandant of the Berlin Defense Area, Gen. Helmuth Weidling, offered to use the forty tanks still at his disposal to spearhead an attempted breakout to the west, across the Havel River bridge at Pichelsdorf, to secure Hitler’s escape from the capital. But Bormann’s planning required that the Führer be flown out, and he needed to be certain of getting Hitler and his party to some location where an aircraft capable of carrying them out of Allied-held Europe could pick them up.

The Bunker’s major weakness was that it had never been designed as a Führerhauptquartier, or command headquarters. After the intensity of Allied bombing forced Hitler and his staff to move underground permanently in mid-February 1945, the means of communication were woefully inadequate for keeping in touch with daily developments in the conduct of the war. Bormann had recognized the inadequacy of the communication system early on; the telephone exchange, more suited to the needs of a small hotel, was quite incapable of handling the necessary volume of traffic. A separate room in the Bunker was in use as a telex center, manned by dedicated navy operators with seven machines, three of which were central to the Reichsleiter’s plans.

Bormann had already sent and signed the message "Agree proposed transfer overseas" to the key operatives along the Führer’s planned escape route using the Nazis’ still unbroken cipher, designated "Thrasher" by the British. This cipher was employed by Bormann’s private communications network built around the top-secret Siemens & Halske encryption machine, the T43 Schlüsselfernschreibmaschine. Adm. Hans-Erich Voss, Hitler’s Kriegsmarine liaison officer, had first brought the Siemens & Halske T43 to Bormann’s attention when the latter approached him late in 1944. Bormann needed to establish a totally secure communications network, one that was capable of reaching U-Boats at sea and ground stations in Spain and the Canary Islands and that could relay messages across the Atlantic to Buenos Aires. A modified version of the T43 machine was the answer to his needs. By February 1945, Bormann had taken control of all these adapted machines, and on 15 April, Adm. Voss’s team had installed three of them with their naval operators in the Führerbunker, where they would continue transmitting until Bormann left the Bunker on 1 May.

At least one machine was with the Abwehr operation in Spain, another at the secret outpost Villa Winter on Fuerteventura in the Canary Islands, and yet another in Buenos Aires. Eight of Adm. Karl Dönitz’s U-Boats also carried these top-secret machines. After 20 April, Dönitz had six machines waiting for him at in Flensburg, where he moved his headquarters at the end of the war, thus enabling Bormann to relay the final movement and shipment orders to be carried out by remnants of the U-Boat fleet based at Kristiansand in Norway. With his communications network set up, Bormann could set about organizing how to get the Führer and his party out of Berlin. From January to April 1945, Martin Bormann and his ally Heinrich "Gestapo" Müller were the gatekeepers controlling all access to Hitler. In drawing up the final escape plans, they were assisted by Bormann’s drinking companion, SS Gen. Hermann Fegelein. Since early 1943, Fegelein had been Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler’s liaison officer at the Führer’s court and so was party to many secrets. Moreover, as the husband of Eva Braun’s sister Gretl, and Eva’s close personal friend, Fegelein was one of Hitler’s most trusted "mountain people".

The first essential was to identify a practical location from which the Führer could be flown out and to decide how to get him there. The vast Soviet noose was tightening fast, and the defense of central Berlin was becoming increasingly desperate. In the city as a whole, Gen. Weidling had approximately 45,000 soldiers and 40,000 aging men of the Volkssturm [Home Guard], supplemented by the Berlin police force and boys from the Hitler Youth. On 22 April, SS Gen. Wilhelm Mohnke—an ultraloyal veteran combat officer of the Waffen-SS—had been personally appointed by Hitler as commander of a battle group to defend the government quarter around the Reichstag building and Chancellery, operating independently of Weidling. This Kampfgruppe [Battle Group] Mohnke had fewer than 2,000 men: about 800 from the SS Guard Battalion "Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler"; 600 men from the Reichsführer-SS Escort Battalion [Himmler’s bodyguard unit]; the Führer Escort Company [a mixed army/air force unit]; and various others swept up from replacement depots. In addition, there were supposed to be perhaps 2,000 men of the so-called Adolf Hitler Free Corps, comprising volunteers from all over Germany who had rallied to the Führer’s defense, and even a number of secretaries and other female government staff who would also take up arms. With such meager resources, Weidling and Mohnke faced some 1.5 million Red Army troops of Marshal Koniev’s 1st Ukrainian Front and Marshal Zhukov’s 1st Byelorussian Front

Although Tempelhof and Gatow airports were already either in Soviet hands or under the Soviet guns, there were still a number of temporary landing strips available. The East–West Axis along the Unter den Linden boulevard was still in use by light aircraft, but a last-minute troop landing there on 26 April, by Junkers Ju 52 transports carrying naval troops to join the garrison, had wrecked several aircraft that had run into shell holes, damaging their landing gear and making further 52 transports carrying naval troops to join the garrison, had wrecked several aircraft that had run into shell holes, damaging their landing gear and making further takeoffs impossible.

The Ju 52 Tri-motor was the type most suitable for flying out the Führer and his party; the standard Luftwaffe transport aircraft throughout the war, it was elderly, slow, but extremely robust, could carry up to eighteen passengers, and needed a relatively short takeoff and landing run.

Fegelein had reconnoitered the remaining viable areas for a pickup; the wide boulevard at Hohenzollerndamm was not perfect, but it was the best available. The underground railway system—the U-Bahn—offered a safe route from the government quarter to Fehrbelliner Platz, and from there [so long as the area was still held by German troops] it was a short drive to the proposed landing strip.

An important role is played by the Charlottenburger Chaussee - the so-called Ost-West Achse. Hitler had designated this wide and long boulevard in central Berlin as a takeoff and landing strip in his "order for the preparations of the defence of the Reichs capital".

But no large multi-engined aircraft could hope to land here. Perhaps this is why the authors of "Grey Wolf" would have us believe that the "final" flight was not made from this location.

One of the most "notable" final flights into the centre of Berlin and the East-West Axis was made by Ritter von Greim and Hanna Reitsch.

The Junkers Ju 52 [nicknamed "Tante Ju" was a German trimotor transport aircraft manufactured from 1931 to 1952. It saw both civilian and military service during the 1930s and 1940s. In a civilian role, it flew with over twelve air carriers including Swissair and Deutsche Luft Hansa as an airliner and freight hauler. In a military role, it flew with the Luftwaffe as a troop and cargo transport andbriefly as a medium bomber.

After Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in 1933, Hans Baur became his personal pilot, and Hitler was provided with a personal Ju 52. Named Immelmann II after the

World War I ace Max Immelmann, it carried the registration D-2600.

In September 1939 at Baur's suggestion, his personal Ju 52 Immelmann II was replaced by the four-engine Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor, although Immelman II

remained his backup aircraft for the rest of World War II.

Crucial to the plan was the most up-to-date Intelligence about the situation on the ground, and during his reconnaissance sorties Fegelein had identified an officer whom he trusted to supply it. The twenty-four-year-old SS Lt. Oskar Schäfer, a veteran of France and the Eastern Front as a Waffen-SS infantryman, had been wounded several times.

Now commissioned as a Panzer officer, he was assigned to SS Heavy Tank Battalion 503, and his Tiger II was one of a handful of these 76.9-ton monsters from that unit that were still fighting in the heart of Berlin.

The Tiger II was the successor to the Tiger I, combining the latter's thick armour with the armour sloping used on the Panther medium tank. The tank was protected by 3.9 to 7.3 in of armour to the front. It was armed with the long barrelled 8.8 cm KwK 43 L/71 anti-tank cannon. The chassis was also the basis for the Jagdtiger turretless tank destroyer.

The Tiger II was first used in combat with 503rd Heavy Panzer Battalion during the Allied Invasion of Normandy on 11 July 1944. On the Eastern Front, it was first used on 12 August 1944 by the 501st Heavy Panzer Battalion

It was known under the informal name Königstiger [the German name for the Bengal tiger], often translated literally as Royal Tiger, or somewhat incorrectly as King Tiger by Allied soldiers, especially by American forces.

On 14 November 1944 the 503rd had a total of 39 [instead of the full complement of 45] Tiger IIs and was loaded on to trains on 27 January 1945, and sent to the Eastern Front in the Army Group Vistula sector. By 15 April 1945, it reported a total of 12 Tiger IIs, of which 10 were still operational. The 503rd ended the war fighting in the Battle of Berlin as part of Kampfgruppe Mohnke.

Late on 27 April 1945, Schäfer and two comrades were summoned to the Reich Chancellery Bunker with orders to report directly to SS Gen. Wilhelm Mohnke for a thorough debriefing on the situation at Fehrbelliner Platz and the Hohenzollerndamm. Mohnke closely questioned Schäfer -who had been wounded with first degree burns- about the disposition of his troops and the likelihood of a breakthrough by the "Ivans" attacking his positions.

Schäfer gave as detailed a report as possible: it was his opinion that they could hold the area for no longer than two more days, and the other two officers agreed. After Schäfer had had a night’s rest, Mohnke awarded him the coveted Knight’s Cross, writing the citation into his Soldaten Buch.

Mohnke also enlisted Schäfer's help in the planned breakout from Berlin on 2 May 1945. His Tiger II leading the Mohnke group was hit crossing the Heer Strasse by a Russian JS II tank. Schäfer was again seriously wounded, suffered further burns, temporarily lost his sight and lost his memory.

Schäfer remained in hospital after the end of the war recovering from his wounds, and was not released until 1947.

Heinrich "Gestapo" Müller could now put into effect his and Bormann’s plans for spiriting the Führer out of Berlin—but first, those who had been chosen to escape had to "die". Hermann Fegelein was the first to disappear into the smokescreen of confusion, lies, and cover-ups that would mask the escape of all the main participants.

There would be several versions of Fegelein’s death. One stated that SS Lt. Col. Peter Högl captured him in his Berlin apartment wearing civilian clothes, ready to go on the run with his mistress, variously “identified” as a Hungarian, an Irishwoman married to a Hungarian diplomat, and an Allied secret agent. Fegelein was supposedly carrying quantities of cash, both German and foreign, and also jewelry, some of which allegedly belonged to Eva Braun [though that was also hearsay]. Högl, a former policeman well known to Heinrich Müller, would be shot in the head while fleeing the Bunker and died on 2 May 1945.

After Hitler's death on 30 April, Högl, Ewald Lindloff, Hans Reisser, Heinz Linge, and possibly Sturmbannfuehrer Franz Schädle carried his corpse up the stairs to ground level and through the Bunker's emergency exit to the bombed-out garden behind the Reich Chancellery. There, Högl witnessed the cremation of Hitler and Eva Braun. On the following night of 1 May, Högl joined the break-out from the Soviet Red Army encirclement. After midnight on 2 May 1945, he was wounded in the head while crossing the Weidendammer Bridge, under heavy fire from Soviet tanks and guns, and died of his injuries.

One SS officer claimed to have shot Fegelein before he made it back to the Bunker, while another supposed witness even alleged that Hitler "gunned him down" personally. Most stated that Fegelein had been shot, perhaps after interrogation by Müller, following a summary court-martial presided over by Wilhelm Mohnke—but Mohnke would later deny that the court-martial ever took place.

According to the book "Nazi Millionaires", by Kenneth D. Alford and Theodore P. Savas, Walter Hirschfeld—a former SS officer working for the U.S. Counterintelligence Corps in Germany—interviewed Fegelein’s father Hans in late September 1945. Hans Fegelein stated to Hirschfeld that "I think I can say with certainty that the Führer is alive. I have received word through a special messenger [an SS Sturmbannführer] … after his death had already been announced". The courier reportedly relayed the following message from Hermann Fegelein: "The Führer and I are safe and well. Don’t worry about me; you will get further word from me, even if it is not for some time." The courier "also said that on the day when the Führer, Hermann, and Eva Braun left Berlin … there was a sharp counterattack in Berlin in order to win a flying strip where they could take off". Hirschfeld was said to have been dumbfounded: "Many SS officers claim the Führer is dead and his body was burned!" However, Hans Fegelein allegedly assured him that it was a smokescreen: "They are all trusted and true SS men who have been ordered to make these statements. Keep your eye on South America".

In actuality, Fegelein had flown into Berlin on 25 April on board a Ju 52 put at his disposal by Heinrich Himmler. He went to his apartment and then, while in communication with Bormann and Müller, reconnoitered the temporary landing strip at the Hohenzollerndamm. He would be waiting in the secret escape tunnel to the underground for his sister-in-law and Adolf Hitler. The Ju 52 then returned to its home base at Rechlin, the same airfield Capt. Peter Baumgart is believed to have flown into Berlin from. The same pilot flew the aircraft back into Berlin on 28 April.

Hitler’s personal pilot, SS Gruppenführer Hans Baur, confirmed that Eva Braun’s brother-in-law always flew in a Ju 52, but Baur said he had not seen the landing on the twenty-eighth or had it reported to him. He had accompanied two old flying friends, Hanna Reitsch and Ritter von Greim, to the temporary landing strip at the Brandenburg gate that same night but denied seeing any Ju 52 on the ground. However, Reitsch, who flew out of Berlin on the twenty-eighth with the newly appointed head of the air force, Luftwaffe Chief Ritter von Greim, said that she took off "around midnight" and that just as her Arado AR 96 trainer became airborne they both saw a Junkers-52 transport plane "near the runway.… A lone pilot was standing by in the shadows. He was obviously waiting for somebody". It is possible that Reitsch and von Greim, flying at roof-height to avoid Soviet fighters, could have seen the escape aircraft on the ground at the Hohenzollerndamm, less than ninety seconds away by air from the Brandenburg Gate airstrip. Creating the myth of Fegelein’s execution was the first of Müller’s perfect cover-ups, and it was soon followed by his masterstroke.

Hohenzollerndamm is the name of a wide boulevard in the Wilmersdorf section of southwest Berlin. The nearest wartime airfields were Berlin-Gatow, about 7.5 km WSW of the Boulevard, and Berlin-Tempelhof, about 5 km east of the Boulevard. But both of these airfields could no longer be used after about 22 April as they were under direct Soviet artillery fire and hourly attacks by Soviet fighters and ground attack aircraft. The Germans then began using Berlin's wide boulevards for courier, liaison and med-evac flights, of which there were only a few with these usually being flown at night.

Hanna Reitsch recorded in her memoirs that she, with a heavily bandaged General von Greim by her side, flew out of Berlin from the Tiergarten, at dawn on 30 April 1945, according to her 5 December 1945 press interview. In testimony to Captain Robert F. Work, Chief Interrogator on 8 October 1945, regarding the 'Last Days of Hitler', the departure from the Bunker is stated as after 1:30 am on 30 April 1945.

Just after the stroke of midnight as 28 April, 1945, began, while the rest of the occupants of the Führerbunker were trying to get some sleep, Hitler’s escape got under way. The Führer, his beloved dog Blondi, Eva Braun, Bormann, Fegelein, and six trusted soldiers from the SS Guard Battalion "Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler" slipped quietly away through the Vorbunker and up to his private quarters in the Old Reich Chancellery building. The light concrete panel was slid aside, revealing the secret escape tunnel. At the end of the electrically lit passageway, down a slight incline, they entered the wider space of the third-level bunker. When the party reached the chamber, they found waiting for them two people whom Müller had had brought there from up the tunnel via the underground railway: two doubles—a stand-in for Hitler [probably Gustav Weler] and one for Eva Braun. Gustav Weler had been standing in for Hitler since 20 July 1944, when the Führer had been wounded in the bomb attempt on his life at his Wolf’s Lair field headquarters near Rastenburg in East Prussia. Hitler had suffered recurrent after-effects from his injuries; he tired easily, and he was plagued by infected wounds from splinters of the oak table that had protected him from the full force of the blast. [His use of penicillin, taken from Allied troops captured or killed in the D-Day landings, had probably saved his life].

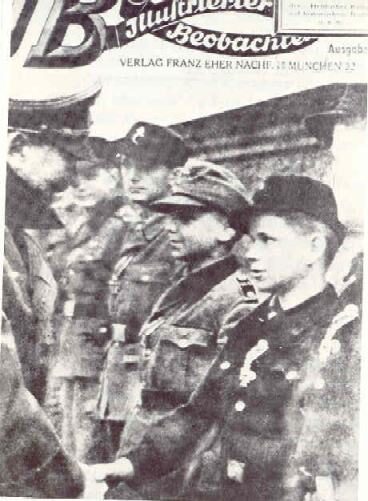

Weler had impersonated Hitler on his last officially photographed appearance, when he handed out medals to members of the Hitler Youth in the Chancellery garden on 20 April 1945.

Weler’s uncanny resemblance to Hitler deceived even those quite close to him, and on that occasion the Reichsjugendführer [Hitler Youth National Leader] Artur Axman was either taken in or warned to play along. The only thing liable to betray the imposture was that Weler’s left hand suffered from occasional bouts of uncontrollable trembling. Bormann had taken Hitler’s personal doctor into his confidence, and SS Lt. Col. Dr. Ludwig Stumpfegger had treated Weler with some success. Weler was often kept sedated, but his trembling became more noticeable when he was under extreme stress

Cover of the 12 April 1945 issue of the "Völkischer Beobachter"

Hitler never actually awarded the medals. this was done by Artur Axmann Class, before Hitler arrived, and the scene was filmed.

This event actually occurred on 20 March 1945.

It was a view was taken from "Die Deutsche Wochenschau" Nummer 755 [The German Weekly Review Number 755], which was the last newsreel circulated to non-occupied Germany in March 1945.

Hitler did decorate Hitlerjugend boys on his birthday on 20 April 1945, but it is an undocumented ceremony in the Ehrenhof of the Chancellery.

Obviously the photos were taken before 20 April if they appeared 8 days earlier in the paper.

Hitler did decorate some Hitler Jugend boys on his birthday, the last issue of the "Völkischer Beobachter" dated 20 April, mentions an awards presentation, but it was not photographed.

Eva Braun’s double was simply perfect. Her name is unknown, but she had been trawled from the "stable" of young actresses that Propaganda Minister Josef Göbbels, the self-appointed "patron of the German cinema", maintained for his own pleasure. The physical similarity was amazing, and after film makeup and hairdressing experts had done their work it was very difficult to tell the two young women apart. Eva paused in the chamber to dash off a note to tell her parents not to worry if they did not hear from her for a long time. She handed it to Bormann, who pocketed it without a word [its charred remains would later be found on the floor—it was too much of a security risk for Bormann to allow it to be delivered]. Bormann then saluted the group, shook Hitler’s hand, and led the counterfeit Führer and his soon-to-be bogus bride back up the tunnel to the Führerbunker.

In the anteroom of the third-level chamber, the fugitives donned steel helmets and baggy SS camouflage smocks.

Hitler carried, slung from his shoulder, a cylindrical metal gas mask case; this contained the painting of Frederick the Great that had hung above his desk. Like his dog, this portrait by Anton Graff went everywhere with Hitler, and his final act in the Bunker had been to remove the 16 x 11-inch canvas from its oval frame, roll it width wise, and slide it carefully into the long-model Wehrmacht gas mask canister. It fitted perfectly.

Hitler gave his favorite portrait of Frederick the Great, painted by Anton Graff in 1780, to his pilot, Hans Baur. Baur was subsequently captured by the Russians during his failed escape attempt from the Bunker, who took the painting from him, but it was since been returned and is currently displayed at Schloss Charlottenburg in Berlin.

The party entered the U-Bahn system near Kaiserhof [today, Mohrenstrasse] station. The walls were painted with a phosphor-based green luminous paint, so the flashlights hanging from the soldiers’ chests bathed the fugitives in an eerie glow. The tunnel was wet, and in places they had to slosh along ankle-deep in water as they made their way to the junction at Wittenbergplatz and on toward Fehrbelliner Platz. The stumbling four-mile journey took three hours, and they were goaded along not only by the sound of bursting shells overhead, but also by echoing small-arms fire in the distance—elsewhere in the system, Soviet and German soldiers were fighting in the railway tunnels. As the group emerged onto the station concourse at Fehrbelliner Platz they were met by Eva’s other sister, Ilse, and by Fegelein’s close friend SS Gen. Joachim Rumohr and his wife. In January 1945, Ilse had fled Breslau by train to Berlin to avoid the advancing Soviet forces. She had dined with Eva at the Hotel Adlon and— despite furious rows with her sister about the conduct of the war—had remained in the city until her brother-in-law Hermann Fegelein sent a detachment of "Leibstandarte" soldiers to fetch her. As for Joachim Rumohr, this was the second time in three months that he would escape from a ruined capital city just ahead of the Red Army. A former comrade of Fegelein’s, Rumohr had been wounded in February 1945 during the bloody fall of Budapest. Erroneously reported to have committed suicide on 11 February to avoid capture by the Russians, he had managed to reach the wooded hills northwest of Budapest and from there escaped to Vienna. Now his friendship with Fegelein guaranteed him the chance of another escape, this time with his wife.

This "factoid" is based on Peter Baumgart referring to a General “Rommer” or “Römer” and his wife being with the escape party. The only Nazi general with a name similar to this was Fegelein’s close friend Rumohr.

"On 1 April 1944 Joachim Rumohr was given the command of the 8th SS Cavalry Division Florian Geyer, being promoted to Standartenführer later the same month. He was mentioned in the Wehrmachtbericht on 9 October 1944. In November 1944 he received his last promotion to Brigadeführer and led his division during the fighting in the Budapest area for which he was awarded the Oakleaves to the Knight's Cross. Rumohr was seriously wounded during the attempt to break out from Budapest, and committed suicide on the 11 February 1945 to prevent his capture by the Soviet Red Army".

When the fugitives reached the main entrance to the Fehrbelliner Platz station, they found three Tiger II tanks and two SdKfz 251 half-track armored personnel carriers waiting to take them on the half-mile drive to the makeshift airstrip on the Hohenzollerndamm.

The flight red signal lamps were placed along an eight-hundred-yard stretch of the wide boulevard, where troops had been set to clearing away debris and filling shell holes. At 3:00 a.m. on 28 April 1945, the lamps were lit, revealing a Junkers Ju 52/3m less than a hundred yards from the parked vehicles. The aircraft, assigned to the Luftwaffe wing Kampfgeschwader 200, had taken off in rainy conditions from Rechlin airfield, sixty-three miles from Berlin, just forty minutes earlier. Rechlin had long been the Luftwaffe’s main test airfield for new equipment designs, but in the closing weeks of the war it had reverted to more essential combat duties. It was one of several bases used by "Bomber Wing 200"—the deliberately deceptive title of a secret special-operations section of the air force commanded from 15 November 1944, by a highly decorated bomber pilot, Lt. Col. Werner Baumbach.

The Ju 52 that landed on the Hohenzollerndamm was flown by an experienced combat pilot and instructor named Peter Erich Baumgart, who now held the parallel SS rank of Captain. More unusually, until 1935 Baumgart had been a South African, with British citizenship. In that year he had left his country, family, and friends and renounced his nationality to join the new Luftwaffe.

In 1943 he had been transferred from conventional duties into a predecessor unit of KG 200; by April 1945 he was thoroughly accustomed to flying a variety of aircraft on clandestine missions, and his reliability had earned him the award of the Iron Cross 1st Class.

Any sortie over Berlin after 26 April was a nightmare of concentrated Soviet flak, huge fires and palls of smoke. There are pictures depicting a wrecked Ju-52 that apparently crashed on take off from the East West Axis on 26 April 1945

German researcher Georg Schlaug writing on April 1945 Berlin sorties in a well known German magazine described how following urgent radio messages from the Bunker were transmitted during the afternoon of 27 April 1945 - "Luftlandemöglichkeit auf der Ost-West Achse muss mit allen Mitteln versucht werden" [landing attempts with all available means must be attempted on the East-West Axis]. The gliders met such heavy fire that every one of them was shot down.

The Ju 52 that had "successfully managed to land" on the Ost-West-Achse on 28 April and then took-off again on the morning of 29 April, was apparently flown by one Oberfeldwebel Böhm from II./TGr 3.

This was reported by another young Ju 52 pilot from this unit, Uffz. Johannes Lachmund who described events in his 2009 memoir. Although a pilot Lachmund flew on this sortie as a gunner. Lachmund records that this mission was flown from Güstrow to Berlin with five aircraft to evacuate high-ranking personnel from Berlin, including Ritter von Greim. As Lachmund reports, three of the five Ju 52s had to return after missed approaches, chiefly because the visibility was so poor from the heavy smoke from the fires everywhere on the ground. One Ju-52 was shot-down by the Soviets during the approach.

Lachmund mentions discussions via telephone from the 'air traffic control' command-post at the Siegessäule [Berlin's Victory column] between Ofw Böhm and the Bunker in the Reichskanzlei. There was apparently some dispute over the passengers to be flown-out, chiefly because Hanna Reitsch wanted to fly out Ritter von Greim herself at the controls of the Arado Ar-96, and not leave Berlin as a passenger on this Ju-52 flight. Eventually, the Ju 52 boarded only a few other wounded passengers but not the VIPs. Because of damage to the 'runway' from shelling, the Junkers transport had only 400 metres in which to get airborne. It is worth noting perhaps that Deutsche Lufthansa record the minimum take-off distance for their lighter [unarmoured and unarmed] Ju 52/3m as 500 metres.

-- Johannes Lachmund : "Fliegen ; Mein Traumberuf – bis zu den bitteren Erlebnissen des Krieges", Verlagshaus Monsenstein und Vannerdat OHG Münster, 2009

Georg Schlaug also records that a Feldwebel Heinz Schäfer witnessed two DFS 230 gliders departing Tarnewitz for Berlin on the afternoon of 29 April 1945. He was shown the glider pilots' Einsatzbefehl [mission orders]; "Gruppe bereithalten, Führer aus Berlin befreien". [stand ready to fly Hitler out].

Baumgart prepared his aircraft for takeoff and his passengers boarded. Baumgart’s orders were to fly to an airfield at Tønder in Denmark, forty-four miles from the Eider River, which runs through northern Germany just below the Danish border. Thankfully, the rain in which he had taken off from Rechlin had now stopped, at least for the time being. Baumgart pushed the throttles forward, and the old "Tante Ju" rattled and shook its way down the patched length of roadway until it lifted its nose into the air.

It would take seventeen minutes to climb to 10,000 feet, where Baumgart could level and settle the Junkers at its cruising speed of 132 miles per hour. It was not until he was airborne and the escape party had removed their helmets that he realized who his main passengers were. Knowing that as soon as the daylight brightened he would be in grave danger from enemy aircraft, Baumgart motioned his copilot to keep a sharp lookout. It was essential to fly as far as possible in darkness at treetop level, given sufficient moonlight, to avoid marauding night fighters protecting the Allied heavy bombers flying between 15,000 and 20,000 feet.

At Rechlin he had been promised an escort of at least seven Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters, but there was no sign of them.

Baumgart would say later that he followed an indirect flight plan, landing for some time at Magdeburg to the west of Berlin to avoid Allied fighters and then flying northward through what the pilot said was an Allied artillery barrage to the Baltic coast.

Magdeburg was occupied by United States troops on 19 April 1945.

His luck held, and he encountered no further Allied aircraft before finally touching down on 29 April at Tønder, Denmark, a former Imperial German Zeppelin base. It was strewn with wrecked machines; just four days earlier, this field and that at Flensburg had been strafed by RAF Tempest fighters [of No. 486 "New Zealand" Squadron] that had destroyed twenty-two aircraft on the ground.

As Baumgart closed down the engines and waited for the ground crew to approach, he caught sight of at least six Bf 109s dispersed around the field—the promised escort. Baumgart unbuckled himself and pulled the flying helmet from his head. In the rear he could hear his passengers getting ready to disembark; they had brought little luggage with them. He climbed out of his seat and walked back down the fuselage, coming to attention and saluting when he reached Hitler.

Maintains Hitler Escaped to Denmark

The Advocate

9 February 1949

LONDON. Captain Peter Baumgart, a former German Luftwaffe pilot, who insisted that he flew Hitler and Eva Braun to Denmark shortly before the fall of Berlin, was today sentenced by a tribunal of three Polish judges to imprisonment for five years for being a member of the S.S.

Baumgart told the tribunal that he was born in South-West Africa, but renounced British citizenship in 1935. He claimed he had shot down 128 Allied aircraft in Crete, Italy, North Africa and the Eastern Front, and was the holder of the Iron Cross and other decorations.

He added that on 25 May 1945 [sic], shortly before the fall of Berlin, Hitler suddenly summoned him and ordered him to fly to Denmark.

Hitler, Eva Braun and a German general, with others, boarded his plane in Berlin, and it took off for Denmark. The plane made a forced landing at Magdeburg, but, upon Hitler's insistence, he flew the following day through an artillery barrage to the Danish shore.

They landed about 44 miles from the Eiter River in a field. Hitler shook hands with him, gave him a cheque for 20,000 Marks, and ordered him to return to Berlin immediately. Baumgart added that he believed Hitler and his party had boarded a submarine.

One of the judges reminded Baumgart that Allied Intelligence reports showed that Hitler and Eva Braun killed themselves on 3 May 1945 [sic], but Baumgart stuck lo his story, adding that, Hitler was "not the kind of man to take his own life".'

Baumgart’s own claims would be separately corroborated by the testimony of a German prisoner of war, Friedrich Argelotty-Mackensen.

The transcript of Mackensen’s interrogation by U.S. Admiral Michael Musmanno records a sighting of Hitler speaking to wounded German soldiers at an airfield, in Tønder, Denmark, three days before he was supposed to have died in Berlin

Musmanno: “Who had command of the plane?”

Mackensen: “Well, of course, I have no idea. I only know that in one of the planes in which Hitler was, that this plane was being flown or piloted by a certain Captain Baumgart. I was lying in the grass and then I was being picked up again. I was carried to some certain place around the plane. Then somebody set me down. All the others were standing there already. Somebody put a Knapsack under my head and then Hitler was standing there and… one moment now. Now, now, at the crucial point! Hitler has said that Admiral Dönitz is now in supreme command of the German army and Admiral Dönitz will enter into unconditional surrender with the Western powers. He is not authorized to surrender to the Eastern powers".

During the Trial Baumbach was doubted and sent to an asylum for psychological evaluation because he maintained that he was the man who facilitated Hitler’s escape. The asylum concluded that this man was very sane and he will maintain his story to his death. The tribunal simply passed him off as a “lunatic” even though their own psychiatrists had testified he was not insane at all. Why was this man's testimony not believed?

According to period newspaper accounts, Baumgart—was briefly imprisoned in Poland after the war, released in 1951, and "never heard of again". However, Baumgart after his release from Polish prison surfaced in the form of a TWA passenger manifest. According to it, Baumgart flew from Europe to New York before catching a flight for Washington, D.C., within weeks of his 1951 parole.

The Führer took a step forward and shook his hand, and Baumgart was surprised to find that he was being slipped a piece of paper, which he put in his trouser pocket to look at later. He watched as the ground crew opened the door from the outside, and Hitler, Eva Braun, Ilse Braun, Hermann Fegelein, Joachim Rumohr, and Rumohr’s wife disembarked.

The party transferred to another Ju 52 to reach the long-range Luftwaffe base at Travemünde, where they boarded a Ju 252 for their flight to Reus, near Barcelona, in Spain.

Capt. Baumgart had been sent for psychiatric tests when he first made these claims which the "Associated Press" and other news outlets reported in contemporary newspapers.

Declared sane, he repeated his story in detail in court in Warsaw. Released in 1951, he was never heard of again.

Friedrich Arthur René Lotta von Argelloty-Mackensen, a twenty-four-year-old SS lieutenant of the "Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler," would claim to have seen would claim to have seen Hitler on Tønder airfield.

Wounded in the fighting around the government quarter on 27 April, he and three comrades, including his superior, SS Lt. Julius Toussaint, had been lucky enough to be put aboard one of the last medical evacuation flights out of Berlin. Mackensen—running a fever and slipping in and out of delirium—was unable to remember the place from which he had left. He described lying on a stretcher in the dimly lit interior of the plane and asking for water.

At Tønder, where he would have to wait for several days, he was carried out of the plane by his comrades and laid on the ground. At some point he heard somebody say, "The Führer wants to speak once more".

Mackensen was moved nearer and laid down again with a Knapsack to pillow his head. Hitler spoke for about a quarter of an hour. He said that Adm. Karl Dönitz was now in supreme command of the German forces and would surrender unconditionally to the Western powers; he was not authorized to surrender to the Soviet Union.

When Hitler finished speaking, the assembled crowd—estimated by Mackensen at about a hundred strong—saluted, and Hitler then moved among the wounded, shaking hands; he shook Mackensen’s, but no words were exchanged. Eva Braun was standing near an aircraft, which Hitler then boarded, and it took off.

For this next leg, on 29 April, the Junkers was not flown by Capt. Baumgart, who was ordered to fly another aircraft back to Berlin for further evacuation flights. The piece of paper in his pocket turned out to be a personal check from Adolf Hitler for 20,000 Reichsmarks, drawn on a Berlin bank. The Führer’s aircraft returned to the field at Tønder, flying over it about an hour later, and a message canister was thrown down onto the airfield; it held a brief note to the effect that Hitler’s party had landed at the coast.