- MAIN INDEX: Adolf Hitler Death and Survival: Legend, Myth and Reality

- New Evidence exposes Hitler’s Secret Refuge after World War II

- Did Hitler Die in the Bunker or Did He Flee to Argentina?

- Is This the Final Proof That Hitler Escaped to Argentina?

- Escape to Argentina

- Following in the Footsteps of Hitler

- Hitler and the Mysteries of the Gran Hotel Viena

- Unredacted FBI File 65-53615

- Declassified CIA File on Hitler

- Hitler's Escape

- Hitler's Escape to South America

- Hitler is Alive

- 17 August 1945

- U-Boote

- Research on Hitler's Escape

- Argentina was Hitler’s Final Home

- "Hunting Hitler"

- Fantastic Voyage of the U-977

- "Grey Wolf – The Escape of Adolf Hitler"

- Hitler Escaped To Argentina Theory

The Bunker [28 April-29 April]

Introduction

On 10 November 2015, the "History Channel" will begin an eight-part series on the possibility that Adolf Hitler did not die in his Berlin Bunker on 30 April 1945, but escaped to South America, called 'Hunting Hitler'. When I learned about the forthcoming television series I remembered that in 2003 the National Archives released the FBI file 65-53615 from the series Headquarters Files from Classification 65 [Espionage] Released Under the Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Disclosure Acts, 1935-1985 [NAID 565806], regarding the multitude of unsubstantiated sightings of Hitler after 30 April 1945. My curiosity prompted me to take a look at the file and found, as I remembered from a decade earlier, that it consisted primarily of rumors regarding Hitler being in South America. I then proceeded to a 1945-1949 State Department Central Decimal File [NAID 302021], 862.002 [Hitler, Adolf] – and found that it contained similar information, as did the files Hitler, Adolf – XE003655 in the Intelligence and Investigative Dossiers Personal Files, 1977-2004 [NAID 645054].

I thought I would write something about the death of Hitler in the Bunker on 30 April, and the subsequent search during 1945 for proof of his death.

-- Dr. Greg Bradsher, Archivist at the National Archives in College Park, MD.

On the evening of 28 April Adolf Hitler, Germany’s Reich chancellor and President, had a lot on his mind. News had arrived during the day that there had been an uprising in northern Italy; Benito Mussolini had been arrested by the pPrtisans; armistice negotiations were being initiated by some of Hitler’s military commanders in Italy; and there had been an attempted coup in Munich.

Karl Friedrich Otto Wolff was a high-ranking member of the Nazi SS, ultimately holding the rank of SS-Obergruppenführer and General of the Waffen-SS. He became Chief of Personal Staff to the Reichsführer [Heinrich Himmler] and SS Liaison Officer to Hitler until his replacement in 1943. He ended World War II as the Supreme Commander of all SS forces in Italy.

When Italy surrendered to the Allies, from February to October 1943 Wolff became the Higher SS and Police Leader of Italy, and served as the Military Governor of northern Italy.

In agreement with Himmler on the issue of futility of continuing the war, from February 1945 Wolff under 'Operation Sunrise' took over command and management of intermediaries including Swiss-national Max Waibel, in order to make contact in Switzerland with the headquarters of the U.S. Office of Strategic Services, under Allen W. Dulles, initially meeting with Dulles in Lucerne on 8 March 1945.

Russian forces were only some 1,000 yards from the Bunker, and the German Ninth Army, which had been ordered to break through the Russian-encircled capital of the Reich to rescue Hitler would most likely not be able to accomplish its mission.

Still, Hitler held a slim hope that Gen. Walther Wenck’s 12th Army, heading toward Potsdam and Berlin, would succeed. [1]

Walther Wenck was the youngest general in the German Army and a highly experienced staff officer during World War II. At the end of the war, he commanded the German Twelfth Army. Wenck ordered his army to surrender to forces of the United States in order to avoid capture by the Soviets. Before surrendering, Wenck played an important part in the Battle of Berlin, and through his efforts aided thousands of German refugees in escaping the rear elements of the Red Army. He was known during the war as "The Boy General".

On 10 April 1945, as General of Panzer Troops, Wenck was made the commander of the German Twelfth Army located to the west of Berlin. The Twelfth Army was positioned to defend against the advancing American and British forces on the Western Front. But, as the Western Front moved eastwards and the Eastern Front moved westwards, the German armies making up both fronts backed towards each other. As a result, the area of control of Wenck's army to his rear and east of the Elbe River had become a vast refugee camp for German civilians fleeing the path of the approaching Soviet forces. Wenck took great pains to provide food and lodging for these refugees. At one stage, the Twelfth Army was estimated to be feeding more than a quarter million people every day.

Berlin's Last Hope

On 21 April, Adolf Hitler ordered SS-General Felix Steiner to attack the forces of Soviet Marshal Georgy Zhukov's 1st Belorussian Front. Zhukov's forces were encircling Berlin from the north.

The forces of Soviet Marshal Ivan Konev's 1st Ukrainian Front were encircling Berlin from the south. Steiner was to attack Zhukov with his 'Army Detachment Steiner'. With few operational tanks and roughly a division's worth of infantry, Steiner declined to attack. Instead, he requested that his "army" be allowed to retreat to avoid its own encirclement and annihilation.

Felix Martin Julius Steiner was a German officer, who became Obergruppenführer of the Schutzstaffel [SS]), General of the Waffen-SS, and a member of the Nazi Party of Nazi Germany. He served in both World War I and World War II and was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords. He contributed significantly, together with Paul Hausser, to the development and transformation of the Waffen-SS, as an armed wing of the Nazi Party's Schutzstaffel, into a multi-ethnic and multinational military force of Nazi Germany.

Steiner was chosen by Heinrich Himmler to oversee the creation of, and command an elite Panzer division, the 5th SS Panzer Division Wiking. In 1943, he was promoted to the command of the III [Germanic] SS Panzer Corps. On 28 January 1945, Steiner was placed in command of the 11th SS Panzer Army, which formed part of a new ad-hoc formation to protect Berlin from the Soviet armies advancing from the Vistula River.

By 21 April, Soviet Marshal Zhukov's 1st Belorussian Front had broken through the German lines on the Seelow Heights. Hitler, ignoring the facts, started to call the ragtag units that came under Steiner's command "Army Detachment" Steiner [Armeeabteilung Steiner].

Steiner, who had always been one of Hitler's favourite commanders, who admired his ''get the job done" attitude and the fact that he owed his allegiance to the Waffen-SS, not the Prussian Officer Corps, was was ordered by Hitler to envelop the 1st Belorussian Front through a pincer movement, to attack the northern flank of the huge salient created by the 1st Belorussian Front's breakout. Steiner's attack was due to coincide with General Busse's Ninth Army, attacking from the south in a pincer attack.

The Ninth Army had been pushed to south of the 1st Belorussian Front's salient. To facilitate this attack, Steiner was assigned the three divisions of the Ninth Army's CI Army Corps: the 4th SS Panzergrenadier Division Polizei, the 5th Jäger Division, and the 25th Panzergrenadier Division. All three divisions were north of the Finow Canal on the Northern flank of Zhukov's salient. Weidling's LVI Panzer Corps, which was still east of Berlin with its northern flank just below Werneuchen, was also to participate in the attack.

The three divisions from CI Army Corps were to attack south from Eberswalde on the Finow Canal towards the LVI Panzer Corps. The three divisions from CI Army Corps were 24 kilometres [about 15 miles] east of Berlin and the attack to the south would cut the 1st Belorussian Front's salient in two.

Steiner called General Gotthard Heinrici and informed him that the plan could not be implemented because the 5th Jäger Division and the 25th Panzergrenadier Division were deployed defensively and could not be redeployed until the 2nd Naval Division arrived from the coast to relieve them. This left only two battalions of the 4th SS Panzergrenadier Division available and they had no combat weapons.

Based on Steiner's assessment, Heinrici called Hans Krebs, Chief of Staff of the German General Staff of the Army High Command [Oberkommando des Heeres or OKH], and told him that the plan could not be implemented. Heinrici asked to speak to Hitler, but was told Hitler was too busy to take his call.

On 22 April 1945, at his afternoon conference, Hitler became aware that Steiner was not going to attack and he fell into a tearful rage. Hitler declared that the war was lost, he blamed the generals, and announced that he would stay on in Berlin until the end and then kill himself.

After the capitulation of Germany, Steiner was imprisoned and indicted as part of the Nuremberg Trials. However, he was cleared of all charges of war crimes and released in 1948. He continued to live in Germany, wrote several books, and participated in organizing support for former Waffen-SS members. He died in 1966.

On 22 April, as Steiner and "Army Detachment Steiner" retreated, Wenck's Twelfth Army became Hitler's last hope to save Berlin. Wenck was ordered to disengage the Americans to his west and, attacking to the east, link up with the Ninth Army of Colonel General [Generaloberst] Theodor Busse. Together, they would attack the Soviets encircling Berlin from the west and from the south. Meanwhile, the XLI Panzer Corps under General Rudolf Holste would attack the Soviets from the north. Unfortunately for the Germans in Berlin, much of Holste's forces consisted of transfers from Steiner's depleted units.

On 26 April General Helmuth Weidling suggested to Hitler a breakout westwards on the night of the 28th by concentrating at one point the bulk of Berlin's troops and spearheading them with 40 battle-worthy Panzers. The German 12th Army at the Elbe River had disengaged from the Americans and was advancing toward Berlin and a link-up was achievable. Hitler, however, vetoed the plan — he would stay, and Berlin would not be surrendered.

"Your proposal is perfectly all right. But what is the point of it all? I have no intentions of wandering around in the woods. I am staying here and I will fall at the head of my troops. You, for your part, will carry on with your defence".

-- Antony Beevor, "Berlin The Downfall 1945"

Hitler also passed up a plan offered by Artur Axman to smuggle Hitler out of the Russian lines under the protection of the Nordland part of the 5th SS Panzer division in the last few days of the war.

Wenck's army, only recently formed, did make a sudden turn around and, in the general confusion, surprised the Russians surrounding the German capital with an unexpected attack. Wenck's forces attacked towards Berlin in good form and made some initial progress, but they were halted outside of Potsdam by strong Soviet resistance.

Neither Busse nor Holste made much progress towards Berlin. By the end of the day on 27 April, the Soviet forces encircling Berlin linked up and the forces inside Berlin were completely cut off from the rest of Germany.

On 28 April, German General and Chief of Staff Hans Krebs, made his last telephone call from the Führerbunker. He called Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel at the new Supreme Command Headquarters in Fürstenberg. Krebs told Keitel that, if relief did not arrive within 48 hours, all would be lost. Keitel promised to exert the utmost pressure on Generals Wenck and Busse.

During the night of 28 April, Wenck reported to the German Supreme Army Command in Fürstenberg that his Twelfth Army had been forced back along the entire front. This was particularly true of XX Corps which had been able to establish temporary contact with the Potsdam garrison. According to Wenck, no attack on Berlin was now possible. This was even more so as support from Busse's Ninth Army could no longer be expected.

Late in the evening of 29 April, Krebs contacted General Alfred Jodl [Supreme Army Command] by radio:

Request immediate report. Firstly of the whereabouts of Wenck's spearheads. Secondly of time intended to attack. Thirdly of the location of the Ninth Army. Fourthly of the precise place in which the Ninth Army will break through. Fifthly of the whereabouts of General Rudolf Holste's spearhead".

In the early morning of 30 April, Jodl replied to Krebs:

"Firstly, Wenck's spearhead bogged down south of Schwielow Lake. Secondly, Twelfth Army therefore unable to continue attack on Berlin. Thirdly, bulk of Ninth Army surrounded. Fourthly, Holste's Corps on the defensive".

As his attempt to reach Berlin started to look impossible, Wenck developed a plan to move his army towards the Forest of Halbe. There he planned to link up with the remnants of the Ninth Army, Hellmuth Reymann's 'Army Group Spree', and the Potsdam garrison. Wenck also wanted to provide an escape route for as many citizens of Berlin as possible.

Arriving at the furthest point of his attack, Wenck radioed the message: "Hurry up, we are waiting for you."

Despite the attacks on his escape path, Wenck brought his own army, remnants of the Ninth Army, and many civilian refugees safely across the Elbe and into territory occupied by the U.S. Army. Estimates vary, but it is likely the corridor his forces opened enabled up to 250,000 refugees, including up to 25,000 men of the Ninth Army, to escape towards the west just ahead of the advancing Soviets.

Escape route

According to Antony Beevor, "Berlin, The Downfall 1945", [Viking 2002], Wenck's eastward attack toward Berlin was aimed specifically at providing the population and garrison of Berlin with an escape route to areas occupied by United States armed forces:

"Comrades, you've got to go in once more", Wenck said. "It's not about Berlin any more, it's not about the Reich any more". Their task was to save people from the fighting and the Russians. Wenck's leadership struck a powerful chord, even if the reactions varied between those who believed in a humanitarian operation and those keener to surrender to the Western allies instead of the Russians.

Wenck was captured and put in a prisoner of war camp. He was released in 1947.

As the evening progressed, more bad news was received in Hitler’s Bunker. During the night Hitler received confirmation that Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, was negotiating with the Western Allies. In response, Hitler ordered Eva Braun’s brother-in-law, SS-Gruppenführer Hermann Fegelein, Himmler’s liaison to Hitler, executed for desertion and treason. [2]

On 27 April 1945, Reichssicherheitsdienst [RSD] deputy commander SS-Obersturmbannführer Peter Högl was sent out from the Reich Chancellery to find Hermann Fegelein who had abandoned his post at the Führerbunker after deciding he did not want to "join a suicide pact". Fegelein was caught by the RSD squad in his Berlin apartment, wearing civilian clothes and preparing to flee to Sweden or Switzerland. He was carrying cash—German and foreign—and jewellery, some of which belonged to Braun. Högl also uncovered a briefcase containing documents with evidence of Himmler's attempted peace negotiations with the Western Allies. According to most accounts, he was intoxicated when arrested and brought back to the Führerbunker. He was kept in a makeshift cell until the evening of 28 April.

That night, Hitler was informed of the BBC broadcast of a Reuters news report about Himmler's attempted negotiations with the western Allies via Count Bernadotte. Hitler flew into a rage about this apparent betrayal and ordered Himmler's arrest. Sensing a connection between Fegelein's disappearance and Himmler's betrayal, Hitler ordered SS-Gruppenführer Heinrich Müller to interrogate Fegelein as to what he knew of Himmler's plans. Thereafter, according to Otto Günsche [Hitler's personal adjutant], Hitler ordered that Fegelein be stripped of all rank and to be transferred to Kampfgruppe 'Mohnke' to prove his loyalty in combat. However, Günsche and Bormann expressed their concern to Hitler that Fegelein would only desert again. Hitler then ordered Fegelein court-martialed.

Fegelein's wife was then in the late stages of pregnancy [the baby was born in early May], and Hitler considered releasing him without punishment or assigning him to Mohnke's troops. Junge—an eye-witness to Bunker events—stated that Braun pleaded with Hitler to spare her brother-in-law and tried to justify Fegelein's actions. However, he was taken to the garden of the Reich Chancellery on 28 April, and was "shot like a dog". Rochus Misch, who was the last survivor from the Führerbunker, disputed aspects of this account in a 2007 interview with "Der Spiegel". According to Misch, Hitler did not order Fegelein's execution, only his demotion. Misch claimed to know the identity of Fegelein's killer, but refused to reveal his name.

Journalist James P. O'Donnell, who conducted extensive interviews in the 1970s, provides one account of what happened next. SS-Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke, who presided over the court martial for desertion, told O'Donnell that Hitler ordered him to set up a tribunal. Mohnke arranged for a court martial panel, which consisted of generals Wilhelm Burgdorf, Hans Krebs, SS-Gruppenführer Johann Rattenhuber, and himself. Fegelein, still drunk, refused to accept that he had to answer to Hitler, and stated that he was responsible only to Himmler. Fegelein was so drunk that he was crying and vomiting; he was unable to stand up, and even urinated on the floor. Mohnke was in a quandary, as German military and civilian law both require a defendant to be of sound mind and to understand the charges against them. Although Mohnke was certain Fegelein was "guilty of flagrant desertion", it was the opinion of the judges that he was in no condition to stand trial, so Mohnke closed the proceedings and turned the defendant over to General Rattenhuber's security squad. Mohnke never saw Fegelein again.

An alternative scenario of Fegelein's death is based on the 1948/49 Soviet NKVD dossier of Hitler written for Josef Stalin. The dossier is based on the interrogation reports of Günsche and Heinz Linge [Hitler's valet]. This dossier differs in part from the accounts given by Mohnke and Rattenhuber. After the intoxicated Fegelein was arrested and brought back to the Führerbunker, Hitler at first ordered Fegelein to be transferred to Kampfgruppe "Mohnke" to prove his loyalty in combat. Günsche and Bormann expressed their concern to Hitler that Fegelein would desert again. Hitler then ordered Fegelein to be demoted and court-martialed by a court led by Mohnke. At this point the accounts differ, as the NKVD dossier states that Fegelein was court-martialed on the evening of 28 April, by a court headed by Mohnke, SS-Obersturmbannführer Alfred Krause, and SS-Sturmbannführer Herbert Kaschula. Mohnke and his fellow officers sentenced Fegelein to death. That same evening, Fegelein was shot from behind by a member of the Sicherheitsdienst. Based on this stated chain of events, author Veit Scherzer concluded that Fegelein, according to German law, was deprived of all honours and honorary signs and must therefore be considered 'a de facto but not de jure' recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross.

Because of the decreasing hope of rescue by his military, the actual and perceived disloyalty of his subordinates [including Hermann Göring], and the desire not to be captured alive, Hitler knew that he soon would have to commit suicide. Before doing so, he wished to marry Eva Braun, and write his final Political Testament and Private Will [NAID 6883511])

Hitler’s secretary, 25-year-old Gertrude Junge, tried that evening to sleep for an hour. Sometime after 11 p.m., she woke up. She washed, changed her clothes, and thought it must be time for the evening tea with Hitler, secretary Frau Gerda Christian, and Hitler’s vegetarian cook Fräulein Constanze Manzialy, as had become a nightly occurrence.

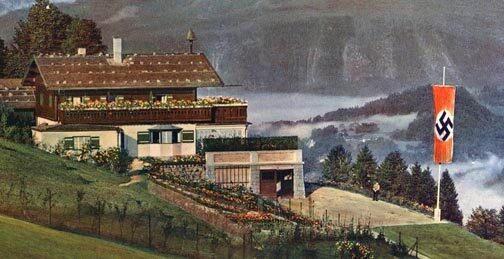

Constanze Manziarly was born in Innsbruck, Austria. She began working as cook and dietitian for Adolf Hitler from his 1943 stays at the Berghof until his final days in Berlin in 1945.

Together with Gerda Christian and Traudl Junge, Manziarly was personally requested to leave the Bunker complex by Hitler on 22 April. However, all three women decided to stay with Hitler until his death.

Manziarly left the Bunker complex on 1 May. Her group was led by SS-Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke, and awkwardly made its way north to a German army hold-out at the Schultheiss-Patzenhofer brewery on the Prinzenallee. The group included Dr. Ernst-Günther Schenck and the female secretaries, Gerda Christian, Else Krüger and Traudl Junge.

Despite claims that she took a cyanide capsule to kill herself on 2 May, the day after the majority of staff abandoned the Berlin stronghold to avoid impending Soviet capture, Junge recounts Manziarly leaving with her group, "dressed too much like a soldier". In 1989, Junge recalled the last time Manziarly was seen was when the group of four women who had been given the task of delivering a report to Karl Dönitz split up, and Manziarly tried to blend in with a group of local women. In her 2002 autobiography "Until the Final Hour", Junge alluded to seeing Manziarly, "the ideal image of Russian femininity, well built and plump-cheeked", being taken into a U-Bahn subway tunnel by two Soviet soldiers, reassuring the group that "[T]hey want to see my papers." She was never seen again.

When she opened the door to Hitler’s study, Hitler came toward her, shook her hand, and asked, “‘Have you had a nice little rest, child?’” Junge replied, “Yes, I have slept a little.” He said, “Come along, I want to dictate something.” This was between 11:30 p.m. and midnight. They went into the little conference room near Hitler’s quarters. She was about to remove the cover from the typewriter, as Hitler normally dictated directly to the typewriter, when he said, “Take it down on the shorthand pad.” She sat down alone at the big table and waited. Hitler stood in his usual place by the broad side of the table, leaned both hands on it, and stared at the empty table top, no longer covered that day with maps. For several seconds Hitler did not say anything. Then, suddenly he began to speak the first words: "My Political Testament". After finishing his Political Testament, according to Junge, Hitler paused a brief moment and then began dictating his Private Will. [3]

Hitler’s Private Will was shorter. It explained his marriage, disposed of his property, and announced his impending death:

"Although during the years of struggle I believed that I could not undertake the responsibility of marriage, now, before the end of my life, I have decided to take as my wife the woman who, after many years of true friendship, came to this city, already almost besieged, of own free will, in order to share my fate. She will go to her death with me at her own wish, as my wife. This will compensate us for what we both lost through my work in the service of my people".

Then after describing his possessions and their disposition, he named Martin Bormann as Executor, with "full legal authority to make all decisions". He concluded: “My wife and I choose to die in order to escape the shame of overthrow or capitulation. It is our wish for our bodies to be burnt immediately on the place where I have performed the greater part of my daily work during the course of my 12 years’ service to my people". [4]

The dictation was completed. He moved away from the table on which he had been leaning all this time and said, “Type that out for me at once in triplicate and then bring it in to me". Junge felt that there was something urgent in his voice, and thought about the most important, most crucial document written by Hitler going out into the world without any corrections or thorough revision. She knew that “Every letter of birthday wishes to some Gauleiter, artist, etc., was polished up, improved, revised—but now Hitler had no time for any of that". Junge took her notepad and typewriter across the hall to type up the Political and Private Wills, knowing that Hitler wanted her to finish as fast as possible. The room she used was next to Reichs Minister of Propaganda Josef Göbbels’ private room. [5]

Eva Braun had spent most of her life waiting for Adolf Hitler and she had agreed to share his fate. She was much more than a dumb blonde reading romance novels and watching films - and she would now be with him forever. It was Hitler's wish that she should be with him in death as she had been for so many years in life. Shortly before his suicide, Hitler said of Eva: "Miss Braun is, besides my dog Blondi, the only one I can absolutely count on ..."

On the morning of 28 April 1945, Eva Braun confided in Hitler's secretary, Frau Traudl Junge:

"That day Eva Braun said something strange to me: she said, you will be shedding tears for me before today is over ... what she actually meant was her marriage to Hitler".

A minor official of the Propaganda Ministry, Walther Wagner, married them in the early hours of 29 April 1945, as a crowning award for her loyalty to the end, while Soviet troops closed on the Reichstag and Chancellery.

The marriage document survived. Eva started to sign her name "Eva Braun" but stopped, crossed out the "B" and wrote "Eva Hitler, born Braun." Göbbels and Bormann signed as witnesses.

The next item of business was the Hitler-Braun marriage. Once Junge departed the conference room, guests began entering to attend the wedding ceremony. The ceremony took place probably at some point between 1 a.m. and 2 a.m. The ceremony lasted no longer than 10 minutes. They then withdrew into their private apartments for a wedding breakfast. Shortly afterward, Bormann, Göbbels, Magda Göbbels, and the secretaries Christian and Junge, were invited into the private suite.

Junge could not come right away as she was typing across the hall. At some point during the party, Junge walked across the corridor to express her congratulations to the newlyweds and wish them luck. She stayed for less than 15 minutes and then returned to her typing.

For part of the time, General of Infantry Hans Krebs, Lt. Gen. Wilhelm Burgdorf, and Lt. Col. Nicholaus von Below [Hitler’s Luftwaffe adjutant] joined the party, as did Werner Naumann [state secretary in the Ministry of Propaganda], Arthur Axmann [Reich youth leader], Ambassador Walter Hewel [permanent representative of Foreign Ministry to Hitler at Führer headquarters], Hitler’s valet Linge, SS-Maj. Otto Günsche [personal adjutant to Hitler], and Manzialy, the cook. They sat for hours, drinking champagne and tea, eating sandwiches, and talking. Hitler spoke again of his plans of suicide and expressed his belief that National Socialism was finished and would never revive [or would not be resurrected soon], and that death would be a relief to him now that he had been deceived and betrayed by his best friends. [6]

Hitler left the party three times to ask how Junge had gotten in her typing. According to Junge, Hitler would look in and say “Are you ready?” and she said, “No my Führer, I am not ready yet". Bormann and Göbbels also kept coming to see if she was finished. These comings and goings made Junge nervous and delayed the process, increasing her distress about the whole situation, and she made several typographical errors. Those were later crossed out in ink. Also complicating her task was the need to add to the political testament the names of some appointments of the new government under Adm. Karl Dönitz. During the course of the wedding party, Hitler discussed and negotiated the matter with Bormann and Göbbels.

While Junge was typing the clean copies of the political testament from her shorthand notes, Göbbels or Bormann came in alternately to give her the names of the ministers of the future government, a process that lasted until she had finished typing. Toward 5 a.m., Junge typed the last of the three copies each of the Political testament and Personal Will. They were timed at 4 a.m., as that was when she had begun typing the first copy of the political testament.

Just as she finished, Göbbels came to her for the documents, almost tearing the last piece of paper from the typewriter. She gave them to him without having a chance to review the final product. She asked Göbbels whether they still wanted her, and he said, “No, lie down and have a rest". The wedding party was ending, and Göbbels took the copies of the documents to Hitler. The documents were ready to be signed. First Hitler signed the personal will, followed by the witnesses Bormann, Göbbels, and von Below. Hitler and witnesses Göbbels, Bormann, Burgdorf, and Krebs then signed the Political Testament. [7]

At around 6am on 29 April regular intense Russian artillery bombardment began with the whole area around the Reich Chancellery and the government district coming under fire. Then in the early morning hours the Soviets launched their all-out offensive against the center of Berlin. Soon the front line was now only some 450 yards from the Chancellery. [8]

Hitler now, in the early morning hours, wanted the three copies of his Political Testament and Private Will to be taken out of Berlin and delivered, to Grand Admiral Dönitz and Field Marshal Ferdinand Schörner [then commander of Army Group Center in Bohemia – who would become the newly appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Army by Hitler’s political testament]. The first person summoned to serve as a courier was thirty-year old Major Willi Johannmeier, Hitler’s adjutant to the Army. At this point he resided in the air-raid shelter under the new Reichs Chancellery, near Hitler’s Bunker.

Ferdinand Schörner was a General and later Field Marshal [Generalfeldmarschall] in the German Army [Wehrmacht Heer] during World War II. He was one of 27 people to be awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit Eichenlaub, Schwertern und Brillanten) and one of the youngest German generals. The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross and its higher grade the Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds was awarded to recognize extreme battlefield bravery or outstanding military leadership.

Schörner was promoted to the rank of Generaloberst in April 1944. In July he became commander of Army Group North, which was later renamed Army Group Courland, where he stayed until January 1945 when he was made commander of Army Group Centre, defending Czechoslovakia and the upper reaches of the River Oder. He became a favorite of high-level Nazi leaders such as Josef Göbbels, whose diary entries from March and April 1945 have many words of praise for Schörner and his methods.

Finally, on 4 April 1945, Schörner was promoted to field marshal and was named as the new Commander-in-Chief of the German Army [Oberbefehlshaber des Heeres] in Hitler's Last Testament. He nominally served in this post until the surrender of the Third Reich on 8 May 1945, but in reality, continued to command his army group, since no staff was available to him. He did not have any discernible influence in the final days of the Reich.

On 7 May, the day General Alfred Jodl, Chief-of-Staff of German Armed Forces High Command [German acroynym OKW], was negotiating the surrender of all German forces at SHAEF, the last the OKW had heard from Schörner was on 2 May. He had reported he intended to fight his way west and surrender his army group to the Americans. On 8 May, an OKW colonel, Wilhelm Meyer-Detring, was escorted through the American lines to contact Schörner. The colonel reported that Schörner had ordered his operational command to observe the surrender, but he could not guarantee that he would be obeyed everywhere. In fact, Schörner ordered a continuation of fighting against Red Army and Czech insurgents. Later that day, Schörner deserted his command and flew to Austria, where he was arrested by the Americans on 18 May, said to have been dressed as a Bavarian non-combatant, behavior for which he had only recently had his soldiers executed. Elements of Army Group Centre continued to resist the overwhelming force of the Red Army liberating Czechoslovakia during the final Prague Offensive. Units of Army Group Centre, the last major German units to surrender, capitulated on 11 May 1945

Schörner did not hesitate to second Hitler's daydreams in the last weeks of the war, agreeing that the Red Army's main objective would be Prague instead of Berlin [in itself a colossal strategic blunder], and so leading him to weaken the already critically thin defense lines in front of the German capital to counter this perceived threat.

At about 8am Burgdorf sent for Johannmeier and told him that an important mission had been entrusted to him. Like Johannmeier, Burgdorf’s room was in the shelter of the new Reichs Chancellery. He was to carry a copy of Hitler’s Political Testament and Private Will out of Berlin, through the Russian lines, and deliver them to Field Marshal Schörner. With him would go two other messengers, bearing similar documents. These were SS-Colonel Wilhelm Zander [an aide to Bormann, representing Bormann] and Heinz Lorenz [an official of the Propaganda Ministry, as representative of Göbbels]. These two men would receive separate instructions. Johannmeier was charged to escort the party on their journey through enemy lines. Burgdorf then gave him the documents he was to carry, along with a covering letter from himself to Schörner:

Führer’s HQ 29 April 1945

Dear Schörner

Attached I send you by safe hands the Testament of our Führer, who wrote it today after the shattering news of the treachery of the RF SS [Himmler]. It is his unalterable decision. The Testament is to be published as soon as the Führer orders it, or as soon as his death is confirmed.

All good wishes, and Heil Hitler!

Yours, Wilhelm Burgdorf

Maj. Johannmeier will deliver the Testament.

About the time Burgdorf was meeting with Johannmeier, or perhaps later, Bormann summoned Zander, who, like Johannmeier, resided in the nearby shelter under the new Reichs Chancellery. Bormann gave him his instructions, including that he was to take copies of Hitler’s Private Will and Political Testament to Dönitz. When Zander expressed his desire to stay, Bormann went to Hitler and explained Zander’s wish. Hitler said he must go and Bormann conveyed this to Zander. Thereupon he handed Zander copies of Hitler’s political and private testaments, and the certificate of marriage of Hitler and Eva Braun. To cover these documents Bormann scribbled a short note to Dönitz:

Dear Grand Admiral

Since all divisions have failed to arrive, and our position seems hopeless, the Führer dictated last night the attached political Testament.

Heil Hitler

Yours, Bormann

After receiving the documents from Bormann, Zander sewed them in his clothing later that morning.

Meanwhile Johannmeier had found Lorenz and told him that a special mission awaited him. Lorenz went to breakfast where he met Zander, who gave him a similar message, and advised him to go to Göbbels or Bormann at once. Lorenz reported to Göbbels sometime before 10am, and was told to go to Bormann and then return. From Bormann, Lorenz received copies of Hitler’s personal and political testaments. Bormann told Lorenz that he had been given this mission because as a young man with plenty of initiative, it was considered that he had a good chance of getting through. On his return, Göbbels gave his Appendix [to Hitler’s Political Testament] to him. Where Göbbels told him to take it is not totally clear. It seems that he was to take them to Dönitz if possible, or failing him, the nearest German High Command, and if all else failed, he was to publish the wills for historical purposes, and ultimately, it appears that the documents were to end up at the Party Archives in Munich.

When Johannmeier went to see Hitler around 9 am he had the will in his [Johannmeier] possession. Hitler told him that this Testament must be brought out of Berlin at any price, that Schörner must receive it. Hitler expressed his opinion that Johannmeier would succeed in the task and once again stressed the importance of the will reaching the destination which he ordered. Johannmeier said they both realized that they would not see each other again and that this influenced the tone in which they said goodbye. Hitler spoke very cordially. Hitler shook his hand. Johannmeier realized that Hitler was going to die. [9]

While Johannmeier, Zander, and Lorenz were getting their instructions, the Russian attack drew ever relentlessly near the Bunker. At about 9am the Russian artillery fire suddenly stopped, and shortly afterwards runners reported to the Bunker that the Russians were advancing with tanks and infantry towards the Wilhelmplatz. It grew quite silent in the Bunker and there was a great tension among its occupants. [10]

About 10am,SS Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke, the commandant of the Chancellery, rang Günsche and informed him that Russian tanks were advancing into Wilhelmstrasse and towards Anhalt station. Günsche reported this to Hitler, who orde red Mohnke to come to him. When Mohnke arrived, Hitler, in the presence of Krebs, Göbbels and Bormann, asked him immediately how long his forces could hold out against the Russians capturing the Bunker. Mohnke replied that unless he received heavy weapons, principally anti-tank weapons and sufficient ammunition, he could only hold out for another 2-3 days at most. At this point, according to Mohnke, the mood of all the leaders was gloomy and “all looked to Adolf Hitler and felt doomed". [11]

Later in the morning Junge went back to Hitler’s Bunker, in order to see whether any changes had taken place. She saw messengers from the fronts coming and going, Hitler was uneasy and walked from one room to another.

Hitler told her he would wait until the couriers had arrived to their destinations with the testaments and then would commit suicide.[12]

On 7 May 1945, SS-Sturmbannführer Dr Helmut Kunz, who had worked in the Reich Chancellery dental surgery from 23 April 1945 onwards, was interrogated by the Soviets. Although he did not profess to know anything pertaining directly to the deaths of Adolf and Eva Hitler, his statement contains a highly significant account of Eva's last known conversation.

The evidence he gave on this occasion cannot be lightly dismissed because it was the first account ever given by a Bunker survivor—meaning that it is the least influenced by accounts given by others. It is also the most reliable, in the sense that the events it discusses had taken place only a week before. Dr Kunz explicitly affirmed seeing Eva Hitler alive on at least two occasions on the evening of 30 April. Dr Kunz told his Russian interrogators that he had seen Eva playing with the Göbbels children on that evening and that a little later, between 10.00 and 11.00 pm, he, Professor Werner Haase and two of Hitler's secretaries had joined her for coffee. On the latter occasion, Eva told Dr Kunz that Hitler was not yet dead but he "would die when he received confirmation that [his] will had reached the person it had been sent to". It is very hard to imagine that Dr Kunz could have been confused about the date, that in such circumstances he could have mistaken Eva Hitler for someone else or that Eva did not actually know whether Hitler was yet dead or not. Moreover, since Hitler's will never reached its intended recipient[s], it is entirely plausible that Hitler would not have decided to die until the last possible moment, which is consistent with a time of 6.30 pm on 1 May.

During the morning General Krebs described to Major Freytag von Löringhoven, his adjutant, the profound disillusionment of Hitler. After the failure of all his effort, Hitler had positively decided to end his life. [13]

At noon, with the Russians closing in on the Bunker, Hitler held his situation conference. Joining Hitler were Bormann, Krebs, Burgdorf, Göbbels, and a few others. During the briefing Hitler was informed that the Soviet forces had begun an encircling attack on the remnants of the Citadel from three sides and resistance could not be maintained much longer. Krebs added that there was no news of the relief Army. [14]

At about noon, Lorenz, in civilian clothes, Zander in his SS uniform, and Johannmeier in military uniform, accompanied by a corporal Heinz Hummerich (a clerk in the Adjutancy of the Führer Headquarters), left the Bunker. Penetrating three Russian rings thrown around the center of the city, they reached Pichelsdorf (at the north end of Havel Lake) by around 4pm or 5pm, , where a battalion of Hitler Youth was holding the bridge against the expected arrival of the relief army. There they slept till night. [15]

Footnotes

[1] Anton Joachimsthaler, "The Last Days of Hitler: Legend, Evidence and Truth" [London: Cassell, 2000]; Bernd Freytag von Löringhoven, "In the Bunker with Hitler: 23 July 1944-29 April 1945" [New York: Pegasus Books, 2006]; Gerhard Boldt, "Hitler’s Last Days: An Eye-Witness Account", trans, by Sandra Bance, [Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military Classics, 2005].

[2] Erich Kern, 'In the Bunker for the Last Battle', Appendix 1 to Erich Kempka, "I Was Hitler’s Chauffeur: The Memoirs of Erich Kempka", trans. By Geoffrey Brooks [London: Frontline Books, 2010]; Joachimsthaler, "The Last Days of Hitler", Joachim Fest, "Inside Hitler’s Bunker: The Last Days of the Third Reich", trans. By Margot Bettauer Dembo [New York: Farrar, Strauss and Girousx, 2004].

[3] Memorandum, Karl Sussman, CIC Special Agent, Region IV, Garmish Sub-Region, Headquarters Counter Intelligence Corps, United States Forces European Theater to Commanding Officer, Garmish Sub-Region, Subject: Interrogation of Junge, Gertrude, 30 August 1946, File: XA085512, Junge, Gertrude, Intelligence and Investigative Dossiers Personal Files, 1977-2004 [NAID 645054], Record Group 319; [Interrogation of] Gertraud [Gertrude] Junge, Munich, 7 February 1948,, Interrogations of Hitler Associates, Musmanno Collection, Gumberg Library Digital Collections, Duquesne University; Traudl Junge, "Until the Final Hour: Hitler’s last secretary", ed. By Melissa Müller and trans. By Anthea Bell [London: Phoenix, 2004.

[4] Col. C. R. Tuff, Deputy Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, Allied Force Headquarters, Combined Weekly Intelligence Summary No. 60, For week ending 27 February 1946, Part II-General Intelligence, ;The Discovery of Hitler’s Wills', File: Combined Weekly Intelligence Summary, Allied Force Headquarters (NAID 2152314), Publications [“P”] Files, 1946-1951, RG 319; [Interrogation of] Gertraud [Gertrude] Junge, Munich, 7 February 1948, p. 32, Interrogations of Hitler Associates, Musmanno Collection, Gumberg Library Digital Collections, Duquesne University.

[5] [Interrogation of] Gertraud [Gertrude] Junge, Munich, 7 February 1948, Interrogations of Hitler Associates, Musmanno Collection, Gumberg Library Digital Collections, Duquesne University; Junge, "Until the Final Hour".

[6] Points emerging from special interrogation of Else Krüger, 25 September 1945, enclosure to Memorandum, Brigadier [no name given], Counter Intelligence Bureau [CIB], GSI (b), Headquarters, British Army of the Rhine to Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2 [CI], Headquarters, US Forces European Theater, Subject: Investigation into the Death of Hitler, 22 November 1945, Document No. CIB/B3/PF.582, File: Major Trevor-Roper Interrogations, Reports Relating to POW Interrogations, 1943-1945 [NAID 2790598] RG 165; [Interrogation of] Erwin Jakubeck, Munich, 6 February 1948, Interrogations of Hitler Associates, Musmanno Collection, Gumberg Library Digital Collections, Duquesne University; Junge, "Until the Final Hour"; H. R. Trevor-Roper, "The Last Days of Hitler" [New York: The Macmillan Company, 1947]; Heinz Linge, "With Hitler to the End: The Memoirs of Adolf Hitler’s Valet", trans. By Geoffrey Brooks [London: Frontline Books and New York: Skyhorse Publsihing, 2009]; James P. O’Donnell, "The Berlin Bunker" [London: Arrow Books, 1979]; Henrik Eberle and Matthias Uhl, eds., "The Hitler Book: The Secret Dossier Prepared for Stalin from the Interrogations of Hitler’s Personal Aides", trans. By Giles MacDonogh [New York: Public Affairs, 2005]; Anthony Read and David Fisher, "The Fall of Berlin" [New York: Da Capo Press, 1995].

[7] Memorandum, Karl Sussman, CIC Special Agent, Region IV, Garmish Sub-Region, Headquarters Counter Intelligence Corps, United States Forces European Theater to Commanding Officer, Garmish Sub-Region, Subject: Interrogation of Junge, Gertrude, 30 August 1946, File: XA085512, Junge, Gertrude, Intelligence and Investigative Dossiers Personal Files, 1977-2004 (NAID 645054); Col. C. R. Tuff, Deputy Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, Allied Force Headquarters, Combined Weekly Intelligence Summary No. 60, For week ending 27 February 1946, Part II-General Intelligence, “The Discovery of Hitler’s Wills,” File: Combined Weekly Intelligence Summary (NAID 2152314); [Interrogation of] Gertraud [Gertrude] Junge, Munich, 7 February 1948, Interrogations of Hitler Associates, Musmanno Collection, Gumberg Library Digital Collections, Duquesne University; Junge, "Until the Final Hour"; Trevor-Roper, "The Last Days of Hitler".

[8] Boldt, "Hitler’s Last Days"; Eberle and Uhl, eds., "The Hitler Book"; Joachimsthaler, "The Last Days of Hitler".

[9] Text of letter from Gen. Burgdorf to Field Marshal Schörner accompanying Hitler’s Political Testament [Johannmeier’s copy], Appendix to Third Interrogation of Willi Johannmeier, 1 January 1946, at CIB, BAOR [British Army of the Rhine], File: Johannmeier, Willi – XE013274 [NAID 7359546)] Memorandum, Karl Sussman, CIC Special Agent, Region IV, Garmish Sub-Region, Headquarters Counter Intelligence Corps, United States Forces European Theater to Commanding Officer, Garmish Sub-Region, Subject: Interrogation of Junge, Gertrude, 30 August 1946, File: XA085512, Junge, Gertrude, Intelligence and Investigative Dossiers Personal Files, 1977-2004 [NAID 645054]; Col. C. R. Tuff, Deputy Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, Allied Force Headquarters, Combined Weekly Intelligence Summary No. 60, For week ending 27 February 1946, Part II-General Intelligence, 'The Discovery of Hitler’s Wills', [based on information supplied by Control Commission (BE) Intelligence Bureau] File: Combined Weekly Intelligence Summary [NAID 2152314]; Third Interrogation of Willi Johannmeier, 1 January 1946, at CIB, BAOR [British Army of the Rhine], File: Johannmeier, Willi – XE013274 (NAID 7359546); Interrogation of General Eckhard Christian and Major Willy Johannmeyer [Johannmeier], Americana Club, Nuremberg, 1330-1830 hours, 10 March 1948, Interrogations of Hitler Associates, Musmanno Collection, Gumberg Library Digital Collections, Duquesne University; Trevor-Roper, "The Last Days of Hitler"; Manuscript Statement by Hitler’s Aide-de-Camp, Otto Günsche, 17 May 1945 in V. K. Vinogrado, J. F. Pogonyi, and N. V. Teptzov, "Hitler’s Death: Russia’s Last Great Secret from the Files of the KGB" [London: Chaucer Press, 2005]; Herman Rothman, ed. by Helen Fry, "Hitler’s Will", The History Press [Glocestershire, United Kingdom, 2009].

[10] Boldt, "Hitler’s Last Days"; Eberle and Uhl, eds., "The Hitler Book".

[11] Handwritten Statement by the Commander of the 'Adolf Hitler” Division', Chief of the Central Berlin Defense Region, Wilhelm Mohnke, Moscow, 18 May 1945 in Vinogrado, Pogonyi, and Teptzov, "Hitler’s Death". According to another source, Mohnke said a day at most. Eberle and Uhl, eds., "The Hitler Book".

[12] Memorandum, Karl Sussman, CIC Special Agent, Region IV, Garmish Sub-Region, Headquarters Counter Intelligence Corps, United States Forces European Theater to Commanding Officer, Garmish Sub-Region, Subject: Interrogation of Junge, Gertrude, 30 August 1946, File: XA085512, Junge, Gertrude, Intelligence and Investigative Dossiers Personal Files, 1977-2004 [NAID 645054].

[13] Freytag von Löringhoven, "In the Bunker with Hitler".

[14] Points emerging from special interrogation of Else Krüger, 25 September 1945, enclosure to Memorandum, Brigadier [no name given], Counter Intelligence Bureau [CIB], GSI (b), Headquarters, British Army of the Rhine to Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2 [CI], Headquarters, US Forces European Theater, Subject: Investigation into the Death of Hitler, 22 November 1945, Document No. CIB/B3/PF.582, File: Major Trevor-Roper Interrogations, Reports Relating to POW Interrogations, 1943-1945 [NAID 2790598]; Trevor-Roper, "The Last Days of Hitler"; Joachimsthaler, "The Last Days of Hitler".

[15] Points emerging from special interrogation of Else Krüger, 25 September 1945, enclosure to Memorandum, Brigadier [no name given], Counter Intelligence Bureau [CIB], GSI (b), Headquarters, British Army of the Rhine to Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2 [CI], Headquarters, US Forces European Theater, Subject: Investigation into the Death of Hitler, 22 November 1945, Document No. CIB/B3/PF.582, File: Major Trevor-Roper Interrogations, Reports Relating to POW Interrogations, 1943-1945 (NAID 2790598); Col. C. R. Tuff, Deputy Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, Allied Force Headquarters, Combined Weekly Intelligence Summary No. 60, For week ending 27 February 1946, Part II-General Intelligence, 'The Discovery of Hitler’s Wills', [based on information supplied by Control Commission (BE) Intelligence Bureau] File: Combined Weekly Intelligence Summary [NAID 2152314]; Trevor-Roper, "The Last Days of Hitler".

The Bunker [29 April-30 April]

Around noon on 29 April 1945, the three couriers with copies of Adolf Hitler’s Private will and Political Testament [and one with his marriage license] left the Berlin Bunker and headed west.

Communications were down, the Soviets were closing in, and many were morbidly anticipating Hitler's suicide.

Major Bernd Freytag von Löringhoven and Rittmeister Gerhardt Boldt requested General Hans Krebs' permission to join the fighting outside. Krebs consulted with Burgdorf, who answered that they should take Lieutenant-Colonel Rudolf Weiß with them. At around 13:30 hours, Hitler approved the action and ordered the men to break through to General Wenck's 12th Army. Hitler further told them: "Send my regards for Walther Wenck. He should make haste, before it is too late".

Hitler asked, "How are you going to get out of Berlin?" When Löringhoven mentioned finding a boat, Hitler became enthusiastic and advised, "You must get an electric boat, because that does not make any noise and you can get through the Russian lines".

For those still in the Bunker, the day was one of feeling trapped and waiting for Hitler to kill himself. Although few believed it would happen, some still were hopeful that the German relief forces would break through the Russian corridor around Berlin and save them. [1]

Hitler ate lunch around 2pm, as usual in the company of the secretaries Gerda Christian and Gertrude Junge. Christian later recalled that nothing was spoken about Hitler’s intention to die or about the manner in which this was to take place. [2]

During the afternoon, communications with the outside world were all but broken and the occupants of the Bunker increasingly became unawares of what was happening on the various fronts. [3] Sometime, probably around 4pm, General Alfred Jodl was able to get a message to the Bunker that in essence said that the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces (OKW) knew nothing about the Ninth Army; believed General Wenck’s Twelfth Army was to be near Potsdam; and OKW could only report a hasty withdrawal westwards by Army Group Vistula. [4]

Around 4 or 4:30pm, at a situation conference, Hitler sent for SS Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke, the commandant of the Chancellery, and requested an update on what was happening in Berlin. Mohnke spread out a map of central Berlin and reported that in the north the Russians had moved close to the Weidendammer Bridge; in the east they were at the Lustgarten; in the south, the Russians were at Potsdamer Platz and the Aviation Ministry; and in the west they were in the Tiergarten, somewhere between 170 and 250 feet from the Reich Chancellery. When Hitler asked how much longer Mohnke could hold out, the answer was "At most twenty to twenty-four hours, my Führer, no longer". [5]

After the situation conference, sometime between 5pm and 6pm, Erich Kempka (Hitler’s chief driver and head of the Führer’s motor pool) visited the Bunker. Outside Hitler’s personal apartment, he stopped to talk. Kempka said Hitler was composed and completely calm. “Even I, who knew him so well, could not read from his attitude the decision he had already taken to end his life.” In his right hand he held a large-scale map of Berlin. His left hand trembled slightly; a condition in the final months that was virtually permanent. Hitler asked Kempka about the status of the motor pool. Kempka replied that the vehicles were in bad condition, destroyed and damaged, but that they were still able to transport the necessary food for the emergency hospitals within the zone of the Chancellery. Hitler then asked him how he saw things, to which Kempka replied that his men were involved in the defense of the Reich Chancellery in the sector between the Brandenburg Gate and Potsdamer Platz. Hitler asked what did his men think. Kempka replied that without exception they were maintaining a bearing beyond reproach and waiting for relief by General Wenck. Hitler responded quickly "We are all waiting for Wenck!" Hitler and Kempka then shook hands, and Hitler spoke a word of encouragement, smiled and then entered his personal room. Kempka left to join his men. In 1948, Kempka said that at no time did Hitler say goodbye or farewell. Kempka speculated that probably Hitler had not set the time of the suicide in his mind yet. [6]

At about 10pm Hitler summoned SS-Gruppenführer Johann Rattenhuber, Chief of the Reich Security Service (responsible for Hitler’s protection) to his room and ordered him to gather the leading personnel of the Headquarters and his close collaborators in his reception room. “I remember,” he later recalled, “that at that moment Hitler looked like a man who had taken a very significant decision. He sat on the edge of a desk, his eyes fixed on one point. He looked determined.” Rattenhuber went to the door to carry out his order, but Hitler stopped him and said, as far as he could remember, the following:

“‘You have served me faithfully for many years. Tomorrow is your birthday and I want to congratulate you now and to thank you for your faithful service, because, I shall not be able to do so tomorrow…I have taken the decision…I must leave this world…”

Rattenhuber went over to Hitler and told him how necessary his survival was for Germany, that there was still a chance to try and escape from Berlin and save his life. ‘What for?" Hitler argued. "Everything is ruined, there is no way out, and to flee means falling into the hands of the Russians…There would never have been such a moment, Rattenhuber," he continued, "and I would never have spoken to you about my death, if not for Stalin and his army. You try to remember where my troops were…And it was only Stalin who prevented me from carrying out the mission entrusted to me from heaven…" According to Rattenhuber, Eva Braun came in from the next room and then for several more minutes Hitler talked of himself – of his role in history, that had been prepared for him by destiny, and shaking hands with Rattenhuber asked him to leave them alone. Rattenhuber thought, after him speaking about his mission from heaven, "He had lost his head from fear". [7]

Shortly after 10 pm Rattenhuber gathered up the individuals Hitler had requested. Among those present for a meeting with Hitler were Josef Göbbels, Martin Bormann, Hans Krebs, Wilhelm Burgdorf, and Colonel Nicolaus von Below, Hitler’s Luftwaffe adjutant. Under fire from machine-guns and grenade-launchers, General Helmuth Weidling, Commandant of Berlin, reached the Bunker covered in mud. The atmosphere in the Bunker was like that of a front-line command post. All who gathered there for the situation report were in a despondent mood. Hitler, “his face still more pinched, was looking fixedly at the map spread before him". Weidling told Hitler that the situation in the city was hopeless, and that the civilian population, in particular, was in a very bad state. He described the deteriorating military situation. The Russians, he said, would reach the Chancellery by 1 May at the latest. Weidling suggested the troops in Berlin try to break out. Hitler replied this was impossible as the soldiers were battle-weary, ill-armed, and without ammunition. He then suggested that Hitler break out of the city with him and the surviving garrison, but Hitler categorically refused. [8]

Still, Weidling persistently asked Hitler to permit a breakout as soon as possible. Hitler, according to Weidling, with bitter irony in his voice, said “‘Look at my map. Everything shown on it is not based on information from the Supreme Command, but from foreign radio station broadcasts. No one reports to us. I can order anything, but none of my orders is carried out any more". Krebs supported Weidling in his attempts to get permission for a breakout. At last it was decided that, as there were no airborne supplies, the troops could break out in small groups, but on the understanding that they should continue to resist wherever possible. Capitulation was out of the question. Weidling felt that although he had failed to get Hitler to call a final halt to the bloodshed, he had managed to persuade him to end resistance in Berlin. [9]

About 10:30 pm an orderly came into the conference and said he had heard a shortwave broadcast reporting news of that Mussolini and his mistress had been executed by Italian partisans. He may or may not have learned that their bodies had been hoisted upside down in Milan and that their bodies were pelted with stones by the vindictive crowd.

Hitler never heard the other news that day from Italy. SS-General Karl Wolff, formerly Himmler's chief aide, had successfully negotiated the unconditional surrender of all German forces in Italy to the Western Allies.

On 29 April, the day before Hitler died, SS General Karl Wolff signed a surrender document at Caserta on behalf of General Heinrich von Vietinghoff, after prolonged unauthorised secret negotiations with the Western Allies, which were viewed with great suspicion by the Soviet Union as trying to reach a separate peace. In the document, Wolff agreed to a ceasefire and surrender of all the forces under the command of Vietinghoff at 2pm on 2 May. Accordingly, after some bitter wrangling between Wolff and Albert Kesselring in the early hours of 2 May, nearly 1,000,000 men in Italy and Austria surrendered unconditionally to British General Harold Alexander at 2pm on 2 May.

In any event Hitler had already determined that his own body should be burned to prevent its exhibition. [10]

After the conference concluded von Below met with Hitler. Earlier during the day von Below had asked Hitler if he would allow him to attempt a breakout to the West. Hitler considered this straightaway and said only that it would probably be impossible. Von Below replied that he thought the way to the West would still be free. Hitler gave him written authority to go and told him he should report to the headquarters of the Combined General Staff, then at Plön, and to deliver a document to Field Marshal Keitel. That afternoon von Below made his preparations and took part in the evening situation conference. Hitler gave him his hand and said only “best of luck.” After saying his goodbyes, Burgdorf handed von Below Hitler’s message. It was addressed to Keitel. In it Hitler stated that the fight for Berlin was drawing to its close, that he intended to commit suicide rather than surrender, that he had appointed Karl Dönitz as his successor, and that Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler had betrayed him. At midnight, with his batman Heinz Matthiesing, von Below left the Bunker and followed roughly the same route as the others [including the three couriers] who had left earlier during the day. [11]

It was apparently after Hitler had said his goodbyes to von Below that Hitler ordered his dog Blondi poisoned. This was in part because he wanted to ascertain the effectiveness of the poison capsules he had been given and also the desire not to have the dog captured by the Russians. After the poison had been administered the dog instantaneously died. Hitler came to see the results and to take his leave of the dog. According to witnesses, Hitler said nothing, nor did his face express any feeling. Afterwards, Hitler returned to his study. Junge later said that after Hitler had seen his dead dog, “His face was like his own death mask. He locked himself into his room without a word". [12]

Blondi was Adolf Hitler's female Alsatian dog [German Shepherd] given to him as a gift in 1941 by Martin Bormann.

By all accounts, Hitler was very fond of Blondi, keeping her by his side, even after his move to the underground Bunker in January 1945, allowing her to sleep in his bedroom. According to Hitler's secretary Traudl Junge, Eva Braun, who preferred her two Scottish Terrier dogs named Negus and Stasi, hated Blondi and was known to kick her under the dining table.

In spring of 1943, Professor Gerdy Troost was in search of a German Shepherd dog of her own after being encouraged by Hitler to get one. He even gave her a book on raising and training dogs written by the "father" of the German Shepherd breed, Rittmeister Max Emil Friedrich von Stephanitz. It was Martin Bormann who eventually arranged for her to meet two dogs at her Munich apartment, out of whom she chose Harrass to be hers.

Gerdy Troost was another woman we do not read about much in history. She was the wife -and after 1934 the widow- of Ludwig Troost, who had been one of Hitler's favorite architects. Even after his death, Gerdy remained close friends with Hitler and many others of the Nazi party bigwigs, for whom she did extensive interior design work.

In the fall of 1944, Hitler had some special plans for Blondi - he planned to breed her to a suitable male from equally good lines as her own.

Blondi was bred to Harrass [with some difficulty] and at the very beginning of April 1945 had a litter of four puppies in the Bunker in Berlin where Hitler, his staff, and the Göbbels family were staying as the Russians neared the city. Hitler had a box for Blondi and her puppies in the bedroom, though most of the time they had free run of one of the Bunker's bathrooms. The first male puppy of the litter was named Wolf, Hitler's favorite nickname and the meaning of his own first name, Adolf [Noble Wolf], and some witnesses say that Hitler would be found carrying and petting the puppy frequently during those last days.

Fritz Tornow was a Feldwebel in the German Army [Wehrmacht Heer] who served as Adolf Hitler's personal dog assistant and veterinarian.

During the last days of World War II, Tornow was one of the few remaining German personnel in the Führerbunker. During the course of 29 April 1945, Hitler learning that the Soviet Red Army was closing in on his location, strengthened in his resolve not to be captured alive. That afternoon, Hitler expressed doubts about the cyanide capsules he had received through Heinrich Himmler's SS. To verify the capsules' potency, Hitler ordered Dr. Werner Haase to test them on Blondi. Tornow had to force the opening of the dog's mouth while Haase crushed a cyanide capsule in Blondi's mouth. Tornow became visibly upset by these events, more so when the dog died as a result.

According to a report commissioned by Josef Stalin and based on eye witness accounts, Tornow was further mortified when he was ordered to shoot Blondi's puppies. On 30 April, Tornow took each of the four puppies of Blondi's from the arms of the Göbbels children, who had been playing with them, and shot them in the garden of the Reich Chancellery, outside the underground Bunker complex, after Hitler and Eva Braun committed suicide together. He also killed Eva Braun's two dogs, Frau Gerda Christian's dogs, and his own Dachshund by lethal injection. Hitler's nurse, Erna Flegel, said in 2005 that Blondi's death had affected the people in the Bunker more than Eva Braun's suicide had.

On 2 May 1945 the Soviet Army took control of the Bunker complex. Tornow was among only five living occupants; the others were Dr. Werner Haase, nurses Erna Flegel and Liselotte Chervinska, and Johannes Hentschel, the electrical engineer. They all surrendered to the Soviet troops.

Soviet troops later recovered Blondi's body as well as that of one puppy [most likely Wolf] when they searched the area, but never made a mention of any other pups in their records, so it is not known for sure what happened to them.

In the book "The Bunker" by James O'Donnell he states that toward Tornow was led out of the Bunker "raging mad in a makeshift straight jacket".

Tornow was taken by the Soviets to the Lubyanka Prison where he was detained, tortured and interrogated until he was released in the mid-1950s. From the 1960s to mid 1970s he lived in the Paulinenhof, in Orthöve, Hervest-Dorsten, where he produced dog food, and apparently the company still exists today, in Gelsenkirchen.

There are rumors that he later lived in Canada; breeders claiming that he worked for them or gave them dogs.

Blondi was initially buried in a shell crater outside the emergency exit to Hitler's Bunker, and this same burial site was later used to inter the cremated remains of Hitler and Eva Braun. On 30 April 1945, on Hitler's orders, Blondi, Hitler and Eva Braun were cremated with Diesel fuel in the Reich Chancellery garden above his Bunker. The charred corpses were later discovered by the Russians. These remains were allegedly shipped to Moscow for tests that confirmed their identity although some accounts have them being autopsied in a pathology clinic in Buch, a suburb of Berlin.

After the autopsies, Hitler, his wife, Eva Braun and his Propaganda leader, Josef Göbbels were allegedly buried in a series of locations including Buch, Finow and Rathenau [all in East Germany].

In February of 1946, the remains were again moved to a Soviet Smersh facility in Magdeburg. These remains were removed one final time in 1982 [some account say it was as early as 1970] at the request of Yuri Andropov, Secretary General of the USSR, 1982-84. Andropov, former KGB chief, fearing that Neo-Nazi's might discover the location, had the graves opened. All remains [still in a state of decomposition] were ground-up and put into a nearby Danube River tributary. All of these details are in dispute and there are many conflicting 'facts' stated in a variety of sources.

While Hitler was in his room, Frau Junge and Frau Christian were conversing and having coffee with two doctors, when Eva Braun joined them.

She said that Hitler would die when he received confirmation that the documents carried by the couriers had reached the persons they had been sent to.

She also said it would not be difficult to die because the poison had already been tested on a dog, and death would come quickly. [13]

Afterwards, Junge, Christian, and Eva Braun joined Hitler for a bite to eat. Hitler in a calm and deliberate manner said that there was no other way for him, than to commit suicide, because he wanted never, alive or dead, to fall into the hands of the enemy. He knew from the example of Mussolini, how he would be treated. He also said he could not fight with his soldiers, because in case he was wounded, there would not be anybody in his surroundings who would give him the mercy-shot, in case he was unable to do that himself. Hitler repeatedly told them that after he was dead, he wanted to be cremated so that nobody shall find him. He said the best is a shot through the mouth, death was instantaneous. Eva Braun was for taking cyanide and pulled a little brass cylinder out of her dress, asking whether it would hurt and stating that she was afraid to suffer. She added she was ready to die, but it must be painless. Hitler told her that cyanide causes paralysis of the nervous and breathing system and causes death in a few seconds. So Christian and Junge, not expecting anything good from the Russians, asked Hitler for an ampoule of poison. He walked to his bedroom where he got the poison. In handing it to them, he said, “I am sorry that as a parting gesture I cannot hand you a nicer present” and that they were very courageous and he wished his generals would have had so much poise and courage as the women did. [14]

Meanwhile, at 10pm on 29 April the three couriers, Zander, Lorenz, and, Johannmeier, found two boats and pushed out into Havel lake, heading southwards for the Wannsee bridgehead, held by units of the German Ninth Army. In the early hours of 30 April they landed independently, Johannmeier on the Wannsee bridgehead, Lorenz and Zander on the Schwanenwerder Peninsula. There they remained, resting all day in underground Bunkers; and in the evening they reunited, and sailed together to the Pfaueninsel, an island in the Havel. From the Wannsee bridgehead Johannmeier had been able to send a radio message to Dönitz, informing him of their position and asking that an airplane be sent to fetch them. On the Pfaueninsel, Johannmeier and Zander obtained civilian clothing and disposed of their uniforms. [15]

Shortly after midnight of 29 April, Hitler began saying his farewells, realizing he would die on 30 April. These goodbyes were with four or five different groups. [16] They lasted until sometime after 2am. One group consisted of some 20-25 persons who worked in the Reich Chancellery and lived in its underground Bunker. These included the secretaries, many of them Hitler had never met. Another group, again numbering between 20-25 persons, included the officers of his escort commando. In the first instances Hitler shook hands with everybody, thanking each one individually. With the latter group he did not say anything when shaking hands. [17]

When addressing the second group, Hitler, in a very calm and conversational manner, said that he did not wish to deliver himself to the Russians and that he, therefore, was going to end his life, and that he was now releasing them from their oath. He thanked them for their services and wished them all the best on their way to the western powers, for it was his wish that they should try to get through to the Americans or British, but that they should not get into Russian hands, on no account. [18]

During these farewells, Junge and Eva Braun watched from a short distance. The former asked the later if the time had come for her and Hitler to kill themselves. Eva Braun said no, but that she would tell her when the time had come. She added that Hitler still had to say goodbye to those closest to him. At some point in the early hours of 30 April, Rattenhuber, who was celebrating his 60th birthday, left his colleagues and their birthday celebration, and joined Junge and Eva Bruan. They, all from Munich, talked about Munich and Bavaria, and how sad it was to have to die so far from home. [19] Meanwhile, Hitler was preparing to say good bye to those closest to him, knowing for many it would be the last time they would see him alive.

Robert Ritter von Greim, was a Bavarian ace who had scored 25 WWI aerial victories, been awarded a knighthood and the coveted Orden Pour le Mérite. He was the first squadron leader of the new Luftwaffe, appointed by Reichsmarschall Göring.

On 25 April 1945, Col. General von Greim asked Germany's most famous test pilot Hanna Reitsch, knowing of her experience and expertise flying around the capital, to fly him into Berlin in a helicopter, as he had been summoned to a meeting with Hitler. Arriving at Rechlin Air Base, she learned the situation in Berlin had worsened, plus the helicopter they had intended to use had been destroyed. Another pilot was to fly von Greim to Gatow in a single seater Focke-Wulff 190, but Reitsch questioned how he would get from there to the Reich Chancellery. She asked if she could be crammed into the back of the plane, so that, with her knowledge of the Berlin center, she could see that von Greim found his way to the Chancellery. This was done and she describes it as the most terrifying plane ride of her life, as she was completely immobile and sightless the entire time.

Upon landing, they learned that all the approach roads into the city were in the hands of the Russians. They finally decided to try to fly into Berlin in a Fieseler Storch [Fi-156C] and land at the Brandenburg Gate. At 6 p.m. they took off in the only Fieseler Storch left, with Greim at the controls and Reitsch crouched behind him.

Flying through a hail of Soviet anti-aircraft fire, the plane was hit in the engine and fuel tank. An armor-piercing bullet smashed Greim’s right foot, and he passed out.

Red Army troops were already in the downtown area, and Reitch, with her long experience at low altitude flying over Berlin and having already surveyed the road as an escape route with Hitler's personal pilot Hans Baur, using only hand controls, managed to successfully land the Fieseler landed on an improvised airstrip in the Tiergarten near the Brandenburg Gate. The Storch was later destroyed on the ground by Russian artillery.

Reitsch and von Greim made their way to the Führerbunker, and now began events even more dramatic and historic than what Hannah Reitsch had already experienced in her event-packed life. Reitsch and Greim remained in the Bunker until early morning 30 April. Present, along with Hitler and Eva Braun, were the Göbbels with their six children; State Secretary Naumann; Martin Bormann; Hewel from Ribbentrop's office; Admiral Voss as representative from Dönitz; General Krebs of the infantry and his adjutant Burgdorf; Hitler's personal pilot Hans Baur, and another pilot Beetz; SS Obergruppenfüuhrer Fegelein as liaison with Himmler; Hitler's personal Physician, Dr. Stumpfegger; Oberst von Below, Hitler's Luftwaffe Adjutant; Dr. Lorenz representing Reichspresse chief Dr. Dietrich for the German press; two of Hitler's secretaries, and various SS orderlies and messengers.

Outside, SS elite troops were committed to guarding Hitler to the end. Inside, after Greim’s foot was operated on by Hitler’s physician, the Führer came into the room and expressed deep gratitude for his coming, saying that even a soldier had the right to disobey an order when everything indicates it would be futile and hopeless. Hitler then informed Greim of Göring’s betrayal and Greim’s succession to commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe. He said to Greim, “In the name of the German people I give you my hand".

Shocked, both Reitsch and Greim asked to stay with him in the Bunker to the end. Hitler agreed at the time and, later that night, according to Reitsch’s Allied interrogation report, gave Hanna a vial of poison for herself and Greim, as everyone else already had, saying "I do not wish that one of us falls to the Russians alive, nor do I wish our bodies to be found by them.” Reitsch, sobbing, begged her Führer to save himself and not deprive the German people of his life. That, she said, is the will of every German. Hitler answered that, “as a soldier, I must obey my own command that I would defend Berlin to the last.” He explained other things, and told her he still had hope that Wenck’s army could arrive from the South, but this was in case it came to the worst.

Hanna returned to Greim’s bedside and they decided together that should the end really come, they would quickly drink the contents of the vial and then each pull the pin from a heavy grenade and hold it tightly to their bodies.

On the 27 April, Obergruppenführer Fegelein disappeared. Shortly thereafter, he was captured on the outskirts of Berlin disguised in civilian clothes, claiming to be a refugee. Hitler ordered him shot, but this event caused some doubt as to Himmler’s position. And, indeed, on 28 April, a telegram arrived which indicated that Himmler had joined the traitor list by contacting British and American authorities through Sweden to propose a capitulation. This was a personal blow to Hitler, and was followed by the news that the Russians would make a full-force attack on the Chancellery on the morning of 30 April .

Just after midnight on that day, Hitler came to Greim’s room and ordered him to return to Rechlin to muster his planes to destroy the Soviet positions from which they would attack the Chancellery, and also to stop Himmler from succeeding him as Führer, and to rendezvous with Karl Dönitz, who Hitler was convinced was rallying troops for a counter-attack.

On 1 May 1945, Himmler attempted to make a place for himself in the Flensburg government. The following is Dönitz' description of his showdown with Himmler:

"At about midnight he arrived, accompanied by six armed SS officers, and was received by my aide-de-camp, Walter Lüdde-Neurath. I offered Himmler a chair and sat down at my desk, on which lay, hidden by some papers, a pistol with the safety catch off. I had never done anything of this sort in my life before, but I did not know what the outcome of this meeting might be.

"I handed Himmler the telegram containing my appointment. 'Please read this', I said. I watched him closely. As he read, an expression of astonishment, indeed of consternation, spread over his face. All hope seemed to collapse within him. He went very pale. Finally he stood up and bowed. 'Allow me', he said, 'to become the second man in your state'. I replied that was out of the question and that there was no way I could make any use of his services.

"Thus advised, he left me at about one o'clock in the morning. The showdown had taken place without force, and I felt relieved".

— Karl Dönitz, as quoted in "The Decline and Fall of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan".